"Long ago, Ben Graham taught me that 'Price is what you pay; value is what you get.'"

-Warren Buffett1

There are two ways people approach buying a bike. Some want something that is "cheap," others want something that is "nice." Both approaches are totally cool. Unfortunately, what "cheap" and "nice" mean to various people is wildly different. I tend to categorize these two perspectives into two distinct groups: those who want something disposable, and those who want something to last. I use the term "disposable" because some people seek out high-quality, yet very inexpensive, bikes from Craigslist to fix up and take care of, while others will often buy new (and expensive) bikes, but treat them poorly until they have wasted away, at which point they buy a new bike. These two methods involve different expectations, and will affect the type and quality of the bike to purchase. To maximize your value with either method, you will need to know some things about buying a bike. Since I'll be referring to prices that can fluctuate rapidly and can differ in different areas of the country, I want to point out that I'll be referring to prices from 2011 in U.S. dollars, and all prices are only estimates.

When first purchasing a bike, people usually have a general idea of what they want; however, there are many more types of bikes than most people know about. How can people know they don't want something they don't know about? There are enough types of bike such that I feel comfortable saying that if someone wants a bike for some particular use and is willing to pay for it, there is a bike perfectly suited to every need. I'll go through a reasonably in-depth list of the types of bikes out there, as most people aren't even aware that their ideal bike is waiting for them.

I'll start with those who want a cheap, disposable bike. Typically, this person simply isn't ready to commit to cycling; he or she just wants to try it out. Here, I want to make it clear: Bikes are not toys. They are vehicles. If you walk into a bike shop and tell someone that you just want something that does x, y, and z and costs less than $100, the response may be a bit awkward. If the shop is especially helpful, it will probably tell you to try Craigslist or that it's just not possible. There is often a real disconnect between how bicycles are viewed by an avid cyclist and by a layperson; this can make for some uncomfortable conversations during the initial sticker shock, but don't be dissuaded by a rude bike-shop employee. I'm here to help!

Essentially, the cheapest solution is a high-tensile strength steel single-speed (which is a bike with only one gear) or a used bike, and your best vendors will probably be Bikes Direct or Craigslist (respectively). If you live in a large enough city, you will also have the option of a bicycle cooperative. If there is a co-op in your city (you should check2), I highly recommend this route, as you can typically donate money (read: "buy") or volunteer your time in exchange for a solid used bike. Unfortunately, cooperatives are exceedingly rare, though they will only become more common if the demographic of bicycle commuters continues to grow. If you can get to a co-op, do it. It can help you to buy and maintain your bike at essentially no cost.

If you decide to shop on Craigslist, you should expect some immediate maintenance, unless you buy a bicycle that has been well taken care of or rarely used. If you are handy with the Internet and a 15-mm wrench, you should be in good shape. At a bike shop, however, even this minor maintenance may cost more than you paid for the bike. So be very careful with exceedingly inexpensive bikes. Later, I'll discuss some general guidelines and red flags to look for when buying used bikes, but if you really have no idea what you're doing, you should probably only look at single speeds, as they are easier to evaluate.

Now, I'm going to assume that you probably won't practice proper storage (no offense), which also points to buying a single-speed, as even when treated harshly, they tend to operate surprisingly well. The only real downside is if you live in a particularly hilly area, at which point gears start to make more sense. The real irony, unfortunately, is that cheap gear-shifting components tend to rust and wear rapidly. Thus, even if the bike is rarely used, when stored outside, it will still stay in better condition if it is a single-speed.

So, if you want to save yourself the time searching Craigslist takes, just go to Bikes Direct3 and navigate to the "single-speed/fixed-gear/track" section. (It is usually hidden as a subsection of the "road" section. Don't ask me why.) Here you can pick out the cheapest, lightest, and probably best overall value bike they have. It'll run about $300 for a chromoly-steel-frame bike (check the specs section to see what metal the frame and fork are made of). Without getting into the details, chromoly steel is a better alloy; you could buy high-tensile steel if you really don't care about the weight of your bike, though I can assure you that you will prefer chromoly. If you get a single-speed via this method, they will ship you a really decent bike, that will last, for cheap (yes, $300 is cheap for a quality, new bicycle). You will have to assemble it, but they come with simple instructions that anyone with a little patience and a tube of waterproof grease can follow. So browse around until you find something you like.

Finally, please, I beg you, do not buy a bike at a big-box retailer; they will sell you what is known as a "bike-shaped object." Even if it is new, it will probably start breaking down within a few weeks. Seriously, I'm not kidding.

If you aren't constrained by spending the absolute minimum, your choices are significantly greater. Here, I will go into some very specific styles of bikes, but none of these are hard-and-fast distinctions. There can be variations of each style; for example, a hard-tail mountain bike can be turned into more of a city bike if some subtle changes are made to the tires and handlebars. So while I will lay out many different styles, don't think you will be pigeonholed. My favorite variation is the cyclocross bike with city tires and a touring seat; I ride one and it is a remarkably nimble commuter.

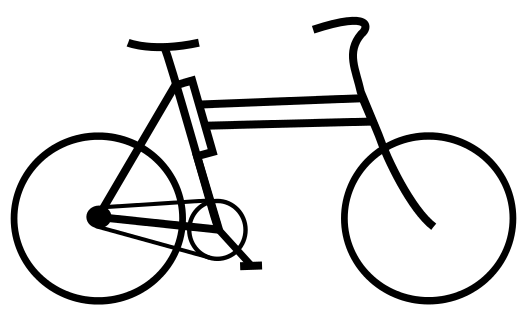

Now before I start talking about different styles of bikes, I want to address a common misconception about step-through frames. There are bicycles designed for women (bicycles whose geometry is subtly adjusted to better suit female proportions), but this has nothing to do with step-through frames. Yes, many women may prefer the extra room because it makes it easier to ride in skirts and dresses, but without a skirt guard, these can be downright dangerous. Step-through frames offer a huge benefit when mounting and dismounting a bicycle loaded with a briefcase or a bag of groceries. The main reason a full-diamond frame is used is that that is the lightest and strongest form a bicycle can take. They are cheaper to manufacture. The idea that step-through frames are only for women is simply a myth. Consider them.

To continue the theme of bicycles for simple transportation, I start with city bikes, or urban bikes, because they are the ideal type of bike for getting around a neighborhood. There are many different styles, but most revolve around the theme of an upright riding position, swooped-back, comfortable handlebars, large saddles, and wide tires. Typically made of steel, they allow for a comfortable ride and will last a lifetime. Their features are ideal for many reasons: The handlebars provide plenty of room for baskets, racks, or headlights; the large saddles provide more comfort for casual riding; and the wider tires reduce PSI, which means they don't need to be re-inflated very often. The three most distinctive city bikes (in my opinion) are the Dutch Opa/Oma, the English three-speed, and the (often modified) classic ten-speed.

The Dutch city bike is, arguably, the most iconic, utilitarian bicycle. Its most recognizable feature is an integrated skirt guard, fender, and taillight. Often they will also have front and rear racks, as they are used as utility bikes in the Netherlands for everything from light shopping to serious cargo. The Oma (step-through version) is especially recognizable for its long, downward curving and step-through top tube, often reinforced to the down-tube. They are traditionally black, often with pale tires.

English three-speeds are quite similar to Dutch bikes. They were a hallmark of cycling, produced in England by companies such as Raleigh. These bikes have similar geometry to Dutch bikes, but the most notable differences are that the step-through frames are much more angular than their Dutch counterparts, they frequently come in earth tones rather than traditional black, and they typically lack a skirt guard. Their main feature is a three-speed internal transmission. This is useful for many reasons: It allows for a chain guard, can change gears while stopped (very useful at red lights), and does not require a delicate derailleur. Though the glory days of the English three-speed have come and gone, its style still abounds, especially with smaller bike manufacturers.

The classic ten-speed bicycle was prolific during the 1970s, and you can still find many of them on Craigslist today. Notable manufacturers are Peugeot, Mercier, Univega, and Nishiki. While technically these were road bikes, they have made a resurgence in America as city bikes, due to their easy conversion to single-speeds and their lasting quality. Buying a different set of handlebars is inexpensive, thus changing the riding position on an old ten-speed is very easy to do, especially since the shifters are typically mounted on the down tube, or stem. If the bike is converted to a single-speed (kits can be purchased for around $30), the shifters can be altogether removed.

Cruisers should also be considered as city bikes. These bikes are notable for their curving frames and fat tires. They often weigh more than their angular counterparts, but are perfectly useful in relatively flat terrain.

I want to point out that this is not an exhaustive list of city bikes by any means. There are also Italian, German, Scandinavian, Chinese, and Japanese city bikes, each with subtly different looks and features. Remember, these are only styles; you can get most of them from an American manufacturers. If you have the time and energy, I'd encourage you to scour the Internet to find the look that suits you best.

Road bikes are generally the standard bike people think of when using the term "bicycle." The idea of a road bike, however, is often far from the reality of the modern technology involved. While they can be affordable, they are performance bikes with price ranges that peak in the tens of thousands. They are often made of carbon fiber, but the lower-end models can be aluminum or steel. There are many different styles, from ultra-fast time-trial bikes to the near-cyclocross versions designed for the Paris-Roubeux race. If you want a bike for performance, you can get lots of help finding exactly what you want at your local bike shop or from your cycling community.

Touring bikes are also a type of road bicycle, though they are specifically designed for long travel. They have geometry for distances and eyelets for racks to store luggage. You can certainly tour your state, if not the entire country, on one of these bicycles. Tourers can ride 50 miles a day or more and still have time to see all the things that a cross-country journey entails. Touring bikes are, in large part, known for their comfort, especially their leather saddles, about which I'll go into more detail later.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the mountain bike became ubiquitous. While still technically a specialty bike, they are frequently converted into city bikes. One of the main issues you will face looking at these bikes is suspension. There are styles with front, rear, and full suspension, or even zero suspension. Mountain bikes are common, but very diverse. Bike shops are great resources for learning about the extensive varieties. Old mountain bikes are common on Craigslist, and often very cheap (especially hardtails from the '90s), so they can be a very good option if you are trying to save money on a quality bike.

Track bikes have had a dramatic return to fashion in the past decade. They are typically fixed-gear, which means that you can't coast. The rear cog is locked and spins with the rear wheel. While this may sound counterintuitive or unpleasant, I can assure you that fixed-gear bicycles are quite pleasant to ride after getting used to the different style of pedaling and adding brakes. Track-bike frames, however, are not defined by the fixed gear, but by their very steep, tight geometry that keeps the rider in a full-prone position. They traditionally do not come with brakes because they are designed for racing on a velodrome. They are performance bikes made for sprinting with full aerodynamics. The casual rider may be very unhappy on a track frame because of its geometry. However, not all bikes advertised as track bikes are actually made for the velodrome. Since their recent rise in fashion, many manufacturers are producing "track" bikes with much more relaxed geometry, often with brakes and in single-speed varieties. One can now get "flip-flop" hubs that allow the rider to ride either fixed- or free-wheel, depending on which side of the hub he or she is using. You can even buy "track" bikes with step-through frames (called "mixtes"), which is almost nonsensical, as a step-through frame would be inefficient in a velodrome. So, because of this current evolution, "track" bikes can be purchased very inexpensively and repurposed for city riding, which is probably a good thing for the cycling community, even if it bothers the taxonomists.

The term "hybrid" is a bit vague; while it technically means some hybrid of two styles of bicycle, generally, when you are asking for a hybrid bicycle you will be directed to either cyclocross bicycles or "hybrids" (which is a style in itself). The style called "hybrid" has become associated with a class of bicycles that is sort of similar to city bikes, but typically have mountain-bike components. There are other types of hybrid variations of bicycles, but these are too extensive for our purposes here.

I'll start with cyclocross bicycles. Cyclocross is a sport popular in Belgium that combines road-racing with riding on muddy trails and leaping off a bike to climb steep hills and jump barriers. It is one of the most dynamic sports in cycling culture, and necessitates a style of bicycle that is part road-racer, part off-road performer. The cyclocross (or "cross") bike is a light but reinforced aerodynamic bike, with wider-than-normal drop bars for better control in the mud; the shifting cables are re-routed so it is easier to carry, and it has knobby but still relatively thin tires. Cyclocross bikes can be found both in geared and single-speed/fixed-gear varieties.

I am particularly fond of the use of cyclocross bikes in urban environments for many reasons. First, they are performance bicycles; as such, they are generally fast and relatively light. Second, they are designed to be carried; this is more useful than you would imagine, especially if your home or workplace requires you to carry your bike up stairs. Next, they are designed for both the road and path; the knobby, slightly wider tires and wider handlebars provide significantly better control for those times when you need to travel on dirt. Plus, they are strong enough to endure the punishment of city riding (jumping curbs, potholes, gravel, etc).

"Hybrids," on the other hand, are a type of bicycle at the other end of the spectrum. They are more of a hybrid between city and mountain bikes. Typically, they have very relaxed geometry and put the rider in a totally upright position. They usually come with mountain-bike components, and, unless they are high-end, are often very heavy. I've never been much of a fan of these, as I see them as flawed versions of city bikes, but I don't want to be too harsh as this is a matter of taste. If you like the look and feel of a hybrid bicycle, you can certainly find very high-quality versions of them.

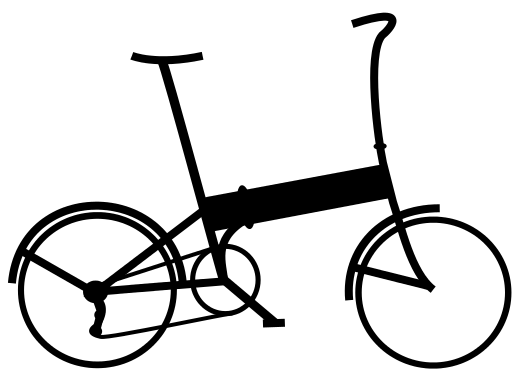

Folding bikes are fairly straightforward; they are bikes that can be collapsed or somehow made smaller for easy portage. While this industry is growing rapidly and their distinctions are immense, there are three main types of folding bikes: small wheel, full wheel, and split-frame folding bikes. Due to their engineering, they tend to be slightly heavier and can be expensive, but there are very affordable models available.

Small-wheeled folding bikes are the most noticeable. While many of them are marvels of engineering, they are generally regarded as visually unappealing (I don't share this view). The better-known brands are unique for their specific features, such as Brompton's super compact profile and Strida's long and slender fold. It should be noted that these bicycles, despite their appearance, ride almost exactly like a normal bike does, though the steering can be a bit tighter. The benefits of these bikes are obvious: portability and storage. Narrow staircases are no problem with folding bikes, so they are very beneficial for highly urban environments. With a small-wheeled folding bike, one often doesn't even need a lock, as the bicycles are allowed inside most shops and offices. They can be stored in a coat closet or in the trunk of a car, and they are almost always allowed on commuter rail. The smallest ones can even be brought onto airplanes as regular checked baggage.

Full-wheel models are much less noticeable than their smaller-wheeled counterparts. Chances are, if you live in a large city, you've probably seen quite a few and simply not realized it. While these can also be used for travel, the main uses for these bikes are getting in and out of buildings and ease in storage. The main benefit of the full wheel is that it is, essentially, indistinguishable from a normal bicycle in its ride. It is simply a bike that happens to fold up.

Split-frame folding bikes are bikes that are cut along their tubing, after which clamps are welded on that can hold the bike together. This allows the cyclist significantly greater ease in travel. Calling them "folding bikes" is slightly incorrect, as they merely are able to be separate into two pieces (they don't actually fold). Since this is often an after-market procedure, the cost and benefits can vary. They are usually only for people who are frequent tourers and are very particular about what they ride. Still, they're worth knowing about in case you have a bike you love and you really want to chop it in half.

Cargo bikes are arguably the most interesting types of bikes that exist. Since they are designed for particular purposes, the number and types of designs are always changing. Some cultures have traditional types of cargo bikes (notably Denmark), but bike companies are sprouting up around America that manufacture many of the best types of cargos from around the world. These bikes are not necessarily expensive, but the nicer, more interesting varieties are quite expensive, as they are generally purchased by businesses for the purpose of moving freight.

The first type of cargo bike is simply a fully equipped bicycle. It will have many of the following: front rack, rear rack, basket, panniers (rack mounting bags), and/or a trailer. These types of bicycles are perfect for shopping and are relatively inexpensive (since they are often just a modification of a regular bicycle). While one may first think that all these gadgets might be ugly, if one has a taste for design, beautiful racks and baskets aren't too hard to find.

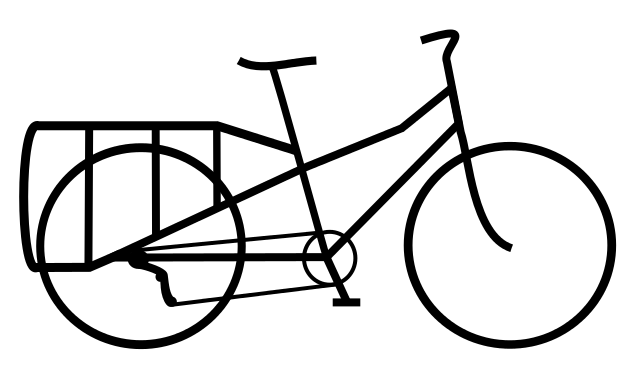

Long-tail bikes, or long bikes, are excellent cargo bikes. This type of bicycle has and extended rear rack and moves the rear wheel significantly farther behind the seat. This provides a large platform for cargo and extended panniers. The rear wheel's position provides added support to the cargo. The primary benefit of this style of cargo bike is that the steering and control stays quite similar to that of a normal bicycle. The other benefit is the cost. Xtracycle sells conversion kits (named FreeRadical)4 that will turn your bicycle into a long-tail bike for as little as $335.

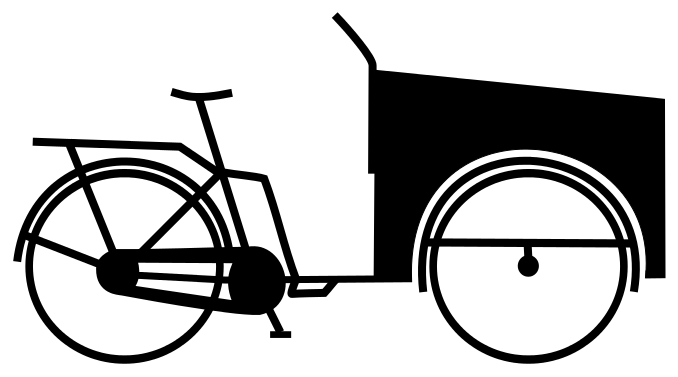

There are two main types of traditional Danish cargo bikes. The first is a three-wheeled cycle; the front two wheels support a very large container. They can also be insulated for cold storage (think: ice cream vendors) or for warm storage, and are effective for business-owners hauling bags of goods across town. While these cargo bikes are large (the front boxes can be as large as shopping carts), they are very quick.

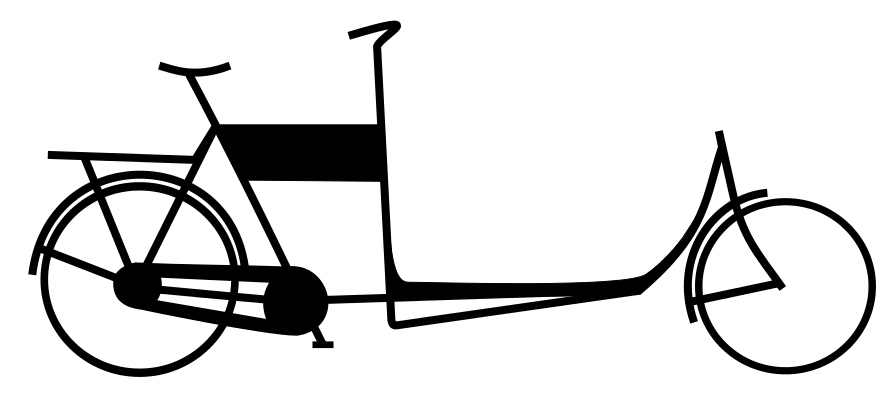

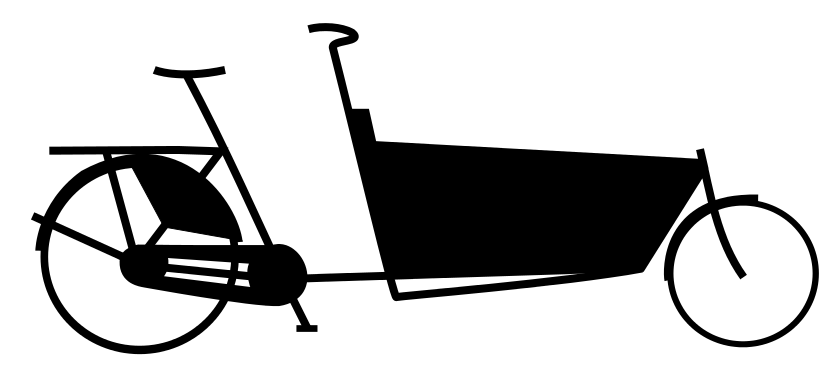

The second type of Danish cargo bike is the flatbed. This true two-wheeled bicycle has a long flatbed between the rider and the smaller front wheel. It is designed to hold enormous amounts of cargo. If you can secure it to the flatbed, you can probably haul it. The rider sits upright behind the goods and rides it like a normal bicycle, unlike its three-wheeled counterparts. They may take a bit of getting used to, but can be are very fast and quite agile.

Similar to the flatbed, the Dutch bakfiets, or box bike, has a box- or wheelbarrow-shaped container where the flatbed would be. These icons of Amsterdam are frequently seen with two or three small children being cycled by their mother or father to the shops or parks. The real benefit of the box bike is its aesthetic appeal; they are beautiful, while staying inherently practical.

Finally, the only truly ugly cargo bicycle is the modern American delivery bicycle. However, what it lacks in beauty, it makes up in ability. Typically, it is some old or stolen mountain bike, a slapdash Frankenbike (a bike assembled from a myriad of random parts from other bikes), or, on occasion, an electric hybrid; the shopkeepers or deliverymen will then modify the front or back racks to have huge baskets that can carry dozens of orders around a city. I must say, while I don't really care for them, one has to admire the ingenuity of the deliveryman who pieced together one of these utilitarian monstrosities.

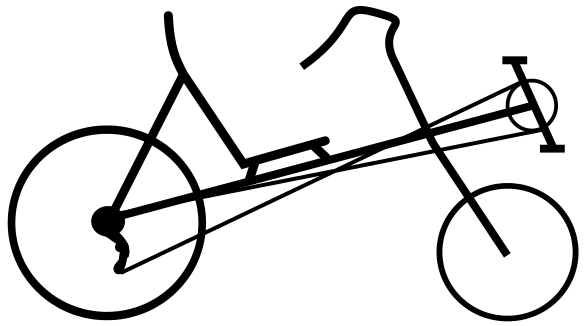

Recumbent bicycles are bicycles that place the rider's feet in front of his or her torso. These are, apparently, more difficult to learn to ride. The have some characteristics that are preferable to standard, prone bicycles. Primarily, they put the rider in a more aerodynamic position. They allow the cyclist to press against the frame of the bicycle to exert more power from each pedal stroke. Lastly, they have a real seat, instead of a saddle, which arguably provides a more comfortable ride.

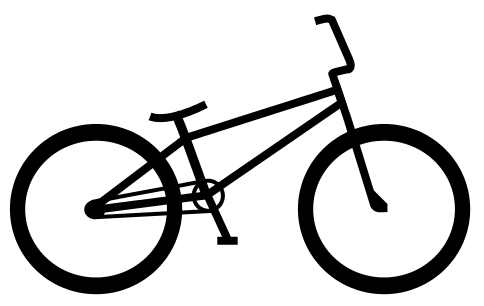

The last bikes I want to talk about are all unique; they are BMX, trials, tall bikes, and swing bikes. BMX should be familiar to most people as they were very popular in the 1980s. They have a very low center of gravity and are used in dirt jumping and other types of "extreme" cycling (I hate that term but have no other way to refer to it). So if that is your thing, you should check them out.

Trials is a type of cycling that is basically defined by it being very difficult. Essentially, it challenges the rider to get over impossibly difficult objects without getting off the bike. Trials bikes usually have very low centers of gravity and step-through frames for better balance. If you have a chance to watch some videos of trials cyclists, you should; it's some of the most impressive bicycle riding that exists.

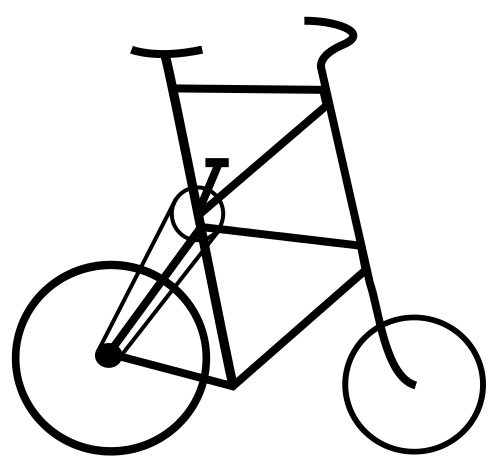

Tall bikes and swing bikes are not produced by any companies for legal reasons, but if you know a welder, you can make yourself one. Tall bikes are made from two frames welded on top of one another, generally with some supports welded on as well. These are modern incarnations of a lamplighter bikes from the era before the lightbulb. They are very fun to ride, putting you up above even large automobiles. Obviously, the downside to them is mounting and dismounting (which can be learned, but is quite difficult at first). For this reason, they tend to be fixed-gear bicycles, as this allows the rider to track stand (a method by which a cyclist can stay upright on a fixed-gear bicycle by rolling subtly back and forth).

Swing bikes are bicycles whose frames have hinges at the handlebars and at the seat. This allows the front wheel to move independently from the rear. I've never ridden one of these, but they appear to be a good time, assuming they're not too tricky to learn. Both tall bikes and swing bikes are very rare to see in public, but if you get a chance, each is quite remarkable.

Bicycles' subtle differences are usually very difficult to notice when shopping for one. Some affect the performance of the bike while others are aesthetic. I briefly want to go over what you will encounter in a basic, starter bicycle: steel, wheels, stems, lugs, and suspension.

First, there is the type of steel used in the frame. While you might be purchasing an aluminum or carbon-fiber bicycle, most intro-level bicycles are made of one of two types of steel: high-tensile (hi-tens) steel or chromoly (CRMO) steel. High-tensile steel is generally considered the lower quality of the two alloys. It is significantly heavier and rusts more readily. However, high-tensile steel's main benefit is that it is significantly cheaper. If you live in a generally flat city and don't see yourself ever needing to carry your bike, then you may not notice the difference. Chromoly steel is light and rust-resistant; this steel will allow a decently maintained bicycle to last a lifetime. It's just better, so make sure you check the specs for this.

Wheel size also varies. The two primary types of wheels are 26-inch and 700C. These sizes are meant to represent the diameter of the tire, 26 inches and 700mm, respectively, but the actual measurements of these wheels can vary wildly, so always consult your bike mechanic before purchasing new tires for your wheels. Typically, 26-inch wheels are for mountain bikes, while 700C are for the road, though there is significant variation. Many touring bikes have 26-inch wheels, and some mountain bikes have wider wheels somewhat equivalent to 700C, called "29ers." Tire widths are still variable within wheel sizes, so remember that buying a road bike doesn't means you need super-narrow tires, and that mountain bikes' wheels can be repurposed for the road. This choice of wheel size, however, is probably moot for most new-bike purchases, as most frames will only fit one type of wheel, but be aware of the wheel size when buying a used bike or any after-market components.

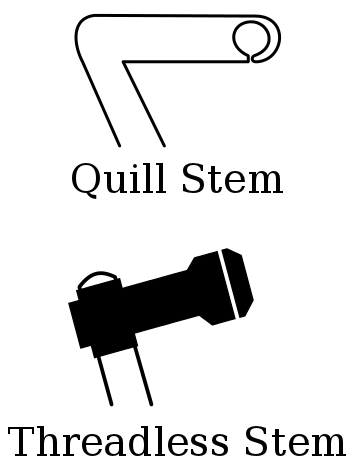

There are also two main types of stems to choose from. The stem is what connects your handlebars to your fork. Traditionally, stems were all quill stems (sometimes called threaded stems), but due to changes to bicycle design, there are also threadless stems. Each type of stem is specific to a type of fork. There are adapters, but it's not very practical to try and switch between the two. Quill stems usually have an aesthetic "7" shape and connect to handlebars via a pinch bolt. Threadless stems are often preferred because they typically have a "pop top" (also called a pillow block) connection to the handlebars. Stems with a pinch bolt require the cyclist to feed the handlebars snugly through the stem, after which the pinch bolt is tightened to hold the bars in place. This requires the cyclist to remove everything from the handlebars when removing them. A pop top has a faceplate that simply unscrews, allowing extremely easy access to the handlebars. If you plan on swapping your handlebars with any regularity, then a pop top is indispensable.

Lugs are also a unique feature of a bike. While modern bicycles' tubing is usually welded directly, lugs that connect tubing are commonly found on older or higher-end steel bicycles. Lugs these days are often intricate, beautiful accent pieces on handmade bicycles. While they may be obsolescent, some in the cycling community are still passionate about the aesthetic and functional value of lugs. For those who want that vintage bicycle look, a lugged frame is an absolute requirement.

Finally, there is suspension. Bicycle suspension comes in many variations, but the primary forms you will encounter are fork suspension, rear suspension, and occasionally, saddle suspension. Frame suspension is generally geared toward performance mountain biking. It's often very sophisticated and can be quite expensive. For most urban environments, anything beyond saddle suspension is probably superfluous. Just understand that there is a trade-off between mechanical efficiency and impact dampening. If you live in an area with cobblestones, excessive potholes, or rough trails, it might be worthwhile, but you will be losing valuable energy with every push of the pedals on flat pavement. For all intents and purposes here, buying a quality saddle and adjusting tire pressure will do more for your overall comfort than expensive frame-suspension systems.

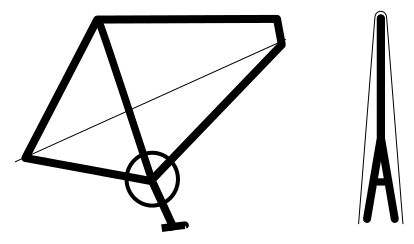

A bicycle's geometry is going to affect how it fits you. You can get more aggressive geometry, which will put you in an aerodynamic position, or you can have more of an upright, relaxed geometry. Regardless of which type of geometry you choose, the bicycle needs to fit. A bike's size should reflect the length of the seat tube, in centimeters, from the center of the weld at the top tube to the center of the bottom bracket; unfortunately, this is rarely the case. Actually, many bike sizes are a measurement of the line between the center of the top and seat tube. Thus, bike fit can be counterintuitive, so it's a good idea to get some help from your mechanic. In addition, I tend to be of the school that thinks top-tube measurement is far more important than seat-tube length when sizing a bike, but top-tube length is not usually a measurement you can get without bringing a tape measure to the store with you.

You can always get fit at a high-end bicycle shop before choosing a bike. A fitting is not just you standing over a bike while the employee nods and says, "Looks good." There will be a machine in the shop that is designed for finding your ideal fit, measured to the millimeter. While this may be impractical for most people, it's an option that does exist, especially if one is going to buy an expensive or custom bike.

Without a machine, the best way to size a bike is to test-ride it. Adjust the saddle to the appropriate height (this is discussed more later, but try to get the seat high enough that you can comfortably pedal with your heels and forward enough that your knee is over the ball of your foot on your downstroke), make sure the bike is safe to ride, and take it out for a short distance. What you should be looking for is how the bike fits your arms and torso. Essentially, if the bike is too big, your torso will feel stretched out and you will feel too much pressure on your wrists. If the frame is too small, your torso will feel bunched up and your butt will feel too much pressure. If the bike is in the right range, you torso should feel comfortable and your weight will be distributed primarily on your legs. Don't worry, though, it doesn't have to fit you exactly; adjustments or different stems allow the handlebars to vary in position. You just want to make sure your bike size is within a good range.

Whether or not to have a derailleur, or derailer (the word just means "thing that causes derailment," but in French), is one of the most important decisions one makes when purchasing a bicycle. Unsurprisingly, some people are quite opinionated about whether or not to have gears. Since the recent rise of the fixed-gear bike and single-speed conversions, a good-spirited rivalry has opened in the bike community. Internal transmissions are the proverbial Switzerland of the two sides, since they have the elements of both. Nevertheless, there are benefits and costs to each.

The choice is heavily dependent on your local topography. Take three American cities: the relatively flat grid of New York City, the occasional gentle hills of Austin, and the (figurative) alpine cliffs of San Francisco. The only need for gearing in New York is the occasional bridge and slight grade; a single-speed will suit anyone who is physically fit, though there may be some soreness when acclimating. An alternative is a three-speed, internal or otherwise, for a little help on the bridges, but this isn't really necessary in Manhattan. Austin can really only be navigated easily with a three-speed at a minimum, unless one is extremely fit. While many Austinites ride the city on fixed-gear and single-speed bicycles, the west side of the city is simply too hilly to negotiate without some gearing. For San Francisco, I would suggest a wide range of gears. Ironically, however, San Francisco has a very large fixed-gear culture; probably because much of San Francisco can be negotiated without directly encountering the massive hills. There seems to be a culture of an altering of routes to suit the cyclist, rather than choosing a bicycle to suit the map. Other than topography, however, the decision between which style to go with is fairly straightforward.

The main benefit of a single-speed is simplicity. A fixed-gear or single-speed drive train is relatively indestructible. Even with enormous wear and tear, the entire unit can be replaced, easily, for under $100. Weight is another benefit. A single-speed drive train is (to my knowledge) the lightest drive train possible; it is also mostly silent. The downside, obviously, is that there is only one gear; however, a consolation is that, depending on the area where you live, you can adjust the gear ratio to suit the environment. Typically, this ratio is measured by the number of teeth on the front chain ring divided by the number of teeth on the rear cog (for example, I generally ride a 46/17 when in Austin, though a 46/22 is probably more suitable for the hills); however, this measurement is somewhat insufficient. The length of your cranks will affect the amount of effort it takes to pedal your bicycle (the technical measurement is inch-pounds, but this is a bit too advanced for our purposes). Anyway, you'll probably want to ask people in your community, or at your bike shop, if you don't know what ratio to use.

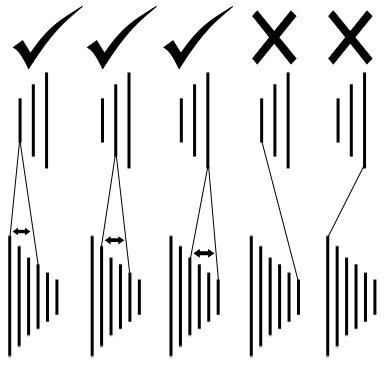

Derailleurs were an advanced technology when they were introduced to the cycling community. The benefits are obvious; with multiple gears, one can adjust one's cadence (the rate at which a person pedals) to suit the grade on any hill. Derailleurs are often misused, though, and abused due to negligence. There are always fewer usable gearings than advertised (e.g., an "18-speed" bicycle probably has 12 usable gears, and a few of those probably overlap). The reason is that the cyclist should keep the chain in a reasonably straight line between the front and rear chain rings. This means that when the inside of the front chain ring is used (typically the smallest ring in front), the chain should be shifted to the inside of the rear cassette as well (typically the largest ring in back), and vice versa. The idea is to keep the chainline relatively straight. If this isn't done, the chain is stretched sideways and can damage the cassette.

The disadvantages of derailleurs, however, are significant. First, one cannot shift gears when stopped. This can be very problematic in a city. Next, they require maintenance. Without proper maintenance, they will rapidly fall in to disrepair (though a tune-up will usually fix this). The problem is compounded in that derailleurs are a bit too complicated for the layperson to fix. While problems incurred by a single-speed are relatively intuitive, there are enough screws and barrels on a typical bicycle transmission to frighten your average beginner, and help from the bike shop costs money.

Finally, not all drive trains are created equal. The derailleur is just one of many components in a multi-gear drive train, and there is a cornucopia of different "levels" of components. This will dramatically affect the price of the bicycle. If you see two seemingly identical bicycles selling for two dramatically different prices, the discrepancy is probably caused by the quality and weight of its drive-train components. To go through all the brands and levels of drive-train components would be unpalatably tedious. So,when you are at your local bike shop, ask about the different levels of components they sell. Generally, you will encounter Shimano products, though SRAM and Campagnolo both make quality components. A quality bicycle will have Shimano's Tiagra (road), ALIVO, or DEORE (mountain) components or better.

Internal transmissions are, in my mind, the happy medium for city cycling. The primary benefit is the ability to shift while stopped; this is crucial in maintaining simplicity in an urban setting. Instead of the constant upward and downward shifting for stop signs and lights, the rider can concentrate on the road rather than on his or her chain's position. Another benefit is that modern internal transmissions aren't exposed to the elements, and they don't require nearly as much maintenance as a drive train with a cassette. They are slightly heavier than their derailleur counterparts, though, but this weight disadvantage is more than made up for by simplicity of use. Traditionally, an internal transmission hub only came with three gear ratios, but one can now get eight or even twelve speeds with an internal transmission. They are, however, expensive. Another downside is their noise; some of the models are quite loud and make clicking noises when in certain gears, though not all of them. Also, they can be broken in a serious crash. While a derailleur system isn't exactly tough, if one were to damage a hub with internal transmission, the entire transmission would be ruined, whereas a derailleur or cassette can easily be replaced on its own.

Regardless of whether you chose a derailleur or internal transmission, you will need shifters. Typically, bikes have trigger shifters (clickable shifters mounted on the handlebars) or friction shifters (metal tabs that move up and down on older bikes). However, there are shifters integrated into brakes, and grip shifters that are integrated where you hold the handlebars. The right shifters can greatly increase the riding experience, so make sure you consider your available options when looking at bikes to purchase.

The price ranges of bicycles for different vendors can be summed up only very generally. As a new cyclist, you will have limited knowledge as to what you are looking for, so here's what to expect. In a bike store, you will probably pay $600 at the bare minimum for anything made of chromoly steel, but I would expect to pay closer to between $800 and $1200. One benefit you should expect is a free cable adjustment between one to three months after purchase. Bicycle cables stretch when they are new and need to be adjusted after the first few months of riding. You may also get a free tune-up after one year of riding; this is somewhere between $60 and $100 of savings (assuming you plan on maintaining your bicycle). Sometimes there will be added benefits from the shop you go to: free adjustments, discounts on accessories or apparel, discounts at its café (many bike shops have commuter cafés), etc. Needless to say, there are some clearly identifiable benefits from buying a new bicycle from a bike shop.

If you go with an online retailer, like Bikes Direct, then you will probably be paying between $250 and $1000 for a standard introductory bike. This is a substantial savings, but there are serious downsides. First, you will have to assemble the bike yourself. It's not too hard, but if you find yourself without a set of Allen wrenches, you'll be paying out of pocket for those. Plus, I hope you are comfortable with looking online for how to make basic adjustments, because you will need to make adjustments to some of the cables within three months, and you will probably have to take it into a store if you don't know how. Don't be surprised if the shop owners charge you a high price for labor, as they will know you purchased your bike from an online discount retailer by its brand name. It'd probably be better if you at least know someone who is handy with bikes or are ready to learn.

If you shop on Craigslist, be ready to get savvy. While the shrewd cyclist can find incredible deals on this website, more often than not you will be rolling the dice. I wouldn't feel comfortable advising anyone to spend more than $350 on a Craigslist bike unless you know what you're doing. You can certainly find bikes for less than that, but you really need to know what to look for to take advantage of these bargains.

Finally, remember to budget for accessories and locks. You will need a good lock, helmet, lights, an air pump, a multi-tool, and a patch kit at minimum. These cost money, and when you skimp here, you put your own safety at risk. So remember to budget $100 at the absolute minimum for these. You can save money if you buy them online before you need them; otherwise, you may end up paying much more to get them immediately at a shop.

At this point, you should have a pretty reasonable idea of what you want. Now you need to know what you don't want. You can't check for everything on a used bike, but you can certainly check for the major issues. It is helpful to bring a friend, a length of string at least double the length of the bike, and a pen or marker to any bike evaluation. Keep an eye out for the following five red flags whenever you are considering a secondhand steel bike. Much of this advice applies to aluminum or carbon fiber, but secondhand steel bikes can be of exceedingly high quality and are common.

First, check the weight of the bicycle. This is generally a good indicator of a quality bicycle. An extremely heavy frame is probably made of high-tensile steel, or possibly worse. This means there may be rust or corrosion out of sight, especially inside the frame if the bike was improperly stored. This can cause numerous headaches, from damage to the bike's structural integrity to parts seizing in the frame. You can check for this by looking inside the frame with a flashlight and trying to adjust anything with threading, but if you are buying a used high-tensile steel bike with any serious age, make sure it is very inexpensive.

Next, check for rust or cracks on the outside of the bicycle. If there are any cracks anywhere on the frame, don't buy the bike. Also, any serious paint loss should be a red flag, as it could lead to rust in the near future. Make sure areas around the lugs or welds are rust-free. Rust on the these sections should be especially worrisome because it is potentially dangerous.

You'll want to check the drive train. This, however, can be difficult if you are not familiar with the way a worn-out drive train looks (this is discussed in Chapter 5). If you are unable to assess the cogs and derailleur, just check for any serious rust or significant hub wobbling as it spins, as this is a very bad sign. You should also try and ride it up an incline and check that the chain doesn't jump under pressure. If it does, this is a worn-out drive train that needs to be replaced. A rusted single-speed drive train is not as serious of a problem because the parts are cheap to replace and a lot more sturdy due to the lack of shifting, but make sure the chainline is straight.

Next, check the bearings. There are ball-bearings in the hubs, bottom bracket, and headset. Make sure these all spin smoothly and give little resistance. Bearings are rather inexpensive to replace if they're is all that's wrong with a nice bike, but bearings are fairly sturdy. If they were seriously damaged for some reason, I'd be concerned about a general lack of maintenance, and what other problems might be lurking.

Finally, to be truly careful, you must check to make sure the fork and rear triangle are straight. Checking the fork is simple; remove the front wheel and reset it. While the owner can make a wheel appear straight in a bent fork, if you replace the wheel yourself while visually checking, you'll be able to see if the wheel is off-kilter in the fork, indicating that it's bent. Also, you will need to check if the wheel is true when doing this (give it a spin and make sure it doesn't wobble much), as this might cause a false positive.

Checking whether the rear triangle is straight is a good idea. The easiest method is to test it with a very long string. It's a bit tricky to describe how to do this, but essentially, you want to measure the distance from the front of the bike to each rear dropout. If that distance is equal, then the rear triangle is fine. If there is any large discrepancy, then do not buy the bike as it will probably not ride straight. The way to do this is by taking a string and starting by holding it next to one dropout, then have a friend take the string around the head tube and bring it to the other rear dropout. Hold both ends firm and have your friend mark the center point at the head tube and then where the string hits the dropouts. Then remove the string and pull it taut without the bike to measure the two distances. If your marks line up, then you are probably safe. If there is any serious discrepancy, beware; either the front or rear triangle is probably bent, and the bicycle might not ride properly.