"I mind my own business, I bother nobody, and what do I get? Trouble."

-The Beggar, Ladri di Biciclette (Bicycle Thieves), 194813

You've seen them. Horrifying carcasses suspended from metal fences and poles; one wheel, often mutilated beyond recognition, hanging onto a lock and frame. Its body is rusted to the point of no return. Shudder to think of the reaction the owner had years ago upon discovering this tragedy. Bicycle theft does happen; perhaps an inevitability for some, though it's mostly preventable.

Here is one of the major unique factors of bicycle transportation: When you get where you are going, a bicycle must be secured. Since automobiles are meticulously registered, theft is more difficult to get away with (often, though, it is still a serious issue in many cities). Insurance is one option, but preventing the theft in the first place is relatively painless procedure; after all, your time and convenience must be worth something. An improperly locked bike isn't going to do the job. Lock poorly and you'll be wasting more time and money than if you'd never locked it at all.

Here's the rub: How you lock your bike is a much more important than simply that you lock your bike. We'll always have the problem of asymmetric information; that is, if you don't know how bikes are stolen, you won't be able to thwart a thief. You need to understand their methods and learn why some methods of locking are weak or even futile. The only way to know whether a bike is poorly locked is to learn what makes the lock inadequate. Now, before I go any further, I must provide a disclaimer. I am not advocating anyone stealing anything. Do not steal bicycles. It is one of the lowest forms of crime. Also, please don't write me letters chastising me for educating people about how they should lock their bikes, and why they shouldn't lock them other ways. Much of this advice may seem obvious, it is followed surprisingly infrequently.

What is the easiest way to steal a bike? Put simply, it is to hop on an unattended, unlocked bike and ride away. Yes, people commonly steal bikes by seeing them unaccompanied and taking them. As I write this, I am literally looking at just such a bike leaning unlocked on a fence outside a café, armed with one of the most expensive locks on the market hanging impotently around its frame, its owner deciding it wasn't worth the five seconds it would take to secure the bike while having a cup of coffee. Today it was not stolen, but such habitual, willful negligence is much more common than one would think. Simply put, always lock your bike when it is unattended, even if you can see it and are going in "for just a few seconds"; besides, by the end of this section, you will know how to secure your bike in fewer than a few seconds.

Careful, though: There are other ways to steal someone's bike in broad daylight without happening upon one unattended. For example, imagine a man on the street asks if he could test-ride your bicycle (after telling you how amazing it looks), and in a brief moment of altruism, you (the throughly flattered victim) consent. Alas, at this point, the thief will ride away quickly, after which it will occur to you what had actually transpired. I think it'd be a bit too harsh to blame the victim here (I don't think I'm quite ready to embrace the cynicism required to admit that no stranger is ever to be trusted), but it's probably safer not to let anyone you don't trust onto your bike (miserly as it may be).

Another method for (not) locking your bike is called "free-locking." This is when one merely locks one of the wheels to the frame and leaves it unattended, though immobilized. The proverb (as popularized by BikeSnobNYC) is that a free-locked bike is free for the taking14. Someone may simply throw the bike in the back of a truck and abscond to some nefarious bicycle (chop) shop where the actual deed is done.

Another method is an insecure anchor (a bike rack or pole, for example) where the post can be removed, making any attempt at locking superfluous. Is the rack you locked to wobbly? Is that signpost even stuck in the ground? How difficult would it be to remove that section of scaffolding? Always check how firm and secure whatever you are locking to is. You may be surprised at how insecure many anchors are. Similarly, after you look down to check how well that sign is planted in the ground, look up and think about how difficult it would be to toss the bike (lock and all) over the top of the sign. A loose chain can often be lofted over parking signs.

The cliché image of bike theft in most people's minds is that of a bicycle secured to a poll, missing a wheel, but in my mind it is always the rear wheel. Why? Because the rear wheel is actually significantly more valuable than the front wheel, it is also less often locked.

When a layperson looks at a rear wheel, they see a lot of gadgets; they see a cassette, axel, and tensioner interwoven by the chain. It looks complicated, so it must be difficult to take that wheel off, right? Wrong. Nothing could be further from the truth. With few exceptions, the rear wheel is just as easy to remove as the front, perhaps requiring a single second to move the chain slightly to one side. Unfortunately, when someone loses his rear wheel (as opposed to the front wheel), he also loses his cassette or free wheel (the pricy little gadget holding the cogs that the chain uses). A painful and expensive tragedy to befall someone, leaving the bike unridable and often left to rust, forgotten.

Obviously, the best way to prevent wheel theft is to lock one's wheels; preventing this misfortune is much less cumbersome than one may imagine. I often encounter labyrinths of cables and chains holding all manner of parts and wheels together. The time it would take to disassemble such meticulous knots of steel and cables would make even Alexander the Great shudder15. The usual solution is a nut and bolt to secure the axle. This is simply an inconvenience for a thief (I'd bet you happen to have a wrench lying around the house, too). A real alternative to the heavy cables, locking skewers, I will address at length later, but suffice it to say there is an elegant solution to this inconvenience.

Finally, don't lock your bike to a tree. Do not lock your bike to a tree. There, I've said it twice. Yes, thieves will cut the tree down. Sure, it's unconscionable, but so is stealing a bike to begin with. Don't believe me? Here is video of it happening in New York City16. The result is that you have a stolen bike and you got a tree got cut down. It is illegal to lock a bike to a tree in most cities for exactly this reason. If you have any decency, find a poll, fence, or bike rack.

There are three primary implements the common thief employs: the pipe, the bolt cutter, and the hacksaw. The first two of these exploit subtle vulnerabilities in reasonably intuitive, but poor, locking systems; the latter is a brute-force method applied to cheap, weak locks. All of them can be frustrated simply by the use of quality locking methods and quality locks.

Let's start with a common type of cable lock. This is typically a very strong cable wrapped in some sort of soft plastic (you've seen it: that one at the store that isn't so expensive). It will have locking mechanisms at both ends, not loops. There is no obvious problem with this lock. It's strong and simple to use; it's intuitive. However, the key weakness is the point at which the lock and cable meet. The spot where a cable connects to the locking ends can be broken if very high torque is applied to the cable. How do you apply that kind of pressure without damaging the bicycle or the rack? You twist it. The cable lock is maneuvered into a position where it can be properly twisted, and a strong pipe is used directly underneath the lock and cable contact points. Imaging putting a rubber band around your wrist, then putting pencil under it and twisting the pencil. Twist ... torque ... torque ... pop! These types of cable locks may keep your bike safe from a passerby or a common unfortunate, but the clever young thief will be delighted at how easily he was able to "liberate" your bike from its fastenings.

The bolt cutter's use is more straightforward. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link; it just so happens here that the weakest link in that monstrous chain is the cheap padlock holding the ends together. Not all chains or padlocks are weak, but the good ones are generally very expensive. The speed at which this method can be employed is impressive. It would only take a matter of seconds to reveal the tool, break the lock, conceal any evidence, and ride away. Here again, it takes little expertise to exploit this weakness; trial and error alone would suffice.

Last, there is the hacksaw; however, this tool is not as efficient as the pipe and bolt cutter. It can take thieves tens of minutes in awkward positions to break a poorly manufactured U-lock, but it's intuitive and readily available. It requires brute force and is probably very difficult to execute; then again, how thick is that steel in the hardware-store U-lock, anyway? Many look like quite a bit of plastic with some metal in the middle. What alloy do they use? Why is it so inexpensive compared to the ones sold at bike stores? Not all U-locks are created equal. The sooner one learns this, the better. (Hopefully, the easy way, instead of staring down at the two pieces of a U-lock cut neatly into three).

The previous examples of theft can be avoided with proper locking technique. Here, however, we will look at some of the more uncommon, and much more sophisticated, methods of theft. There are ways to deter professional thieves, but methods tend to involve trickery and technique rather than hardened steel.

The angle grinder is the powerhouse of the serious thief. The problem is that an angle grinder can cut through even the most advanced U-locks in seconds, serious chains don't stand a chance against one, and even if there were a lock strong enough to withstand it, why not simply cut through the rack anchoring the bike? On the upside, angle grinders are extremely attention-grabbing. They are noisy, send sparks everywhere, and typically require a plug. Most important, they are expensive.

The jack is the U-lock's worst enemy. A hydraulic bottle-jack can be deployed rapidly to bend the U in the U-lock into a variety of unfortunate shapes, dislodging it from its housing. A mechanical scissor-jack can fit in to relatively tight spaces and still create incredibly high pressures. Worst of all, both of these can be employed silently in the middle of the night. It is the jack that makes the beneficial attributes of a good U-lock so counterintuitive (that smaller is better). Remember, a jack can't break a lock it can't fit into. Unfortunately, jacks come in all shapes and sizes, and there is probably some custom jack that can break any type of U-lock. Fortunately, even the most professional of thieves can't carry such an arsenal at all times, and it would be prohibitively expensive to do so as well. Here, good technique can minimize this risk.

Another way to get through a good lock is to just pull it until it snaps. This is how a winch can break your lock. A winch is a hook and cable, typically attached to a vehicle. When you have a bike locked to something relatively solid, the lock can be broken simply by pulling the lock (with the help of a large engine) until, under the extreme tension, it snaps. This is much more slapdash than a jack or angle grinder, because if the bike is anchored to something that isn't very solid, it might just uproot the anchor, which may not be easily removed. While this would technically get the job done, it would still require much more work on the part of the thief. Because this would draw much attention during the day, it is avoided by not having one's bike out overnight.

Another professional tactic of bike thieves is good, old-fashioned burglary. A few years ago, there was a relatively high-profile case within the my local cycling community. Extremely valuable bikes started disappearing from people's homes, strangely, with few traces of break-ins. It turned out that one of the newcomers to the cycling scene was "getting to know" the owners of high-end bikes, casing their houses, and robbing them when they were gone. After a while, he got caught, and had to explain why he had over $50,000 worth of stolen bicycles and equipment in his garage. If your are storing your bike at home (especially in a garage), it's probably a good idea to lock it to something solid just in case. Though it might be considered overkill, it shouldn't take much time at all if done properly.

Finally, there is the professional who steals parts off properly locked bikes on the street. Though this is quite rare, it's worth noting. It is essentially a crime of opportunity; someone can walk up to a well-locked bike with a few Allen wrenches and walk off with highly valuable parts, but considering that your average bike thief wouldn't know the difference between Shimano Dura-Ace STI shifters (that cost hundreds of dollars) and Tektro Aero Brake Levers (that cost tens of dollars), I have to qualify it as something only a professional would attempt. Knowing what parts are worth stealing, how insecure the parts are on the bike, and having the tools on hand to get at them makes this sort of theft exceedingly uncommon. There are more than a few ways to protect oneself, but it's very difficult to protect all the potentially valuable parts on one's bike from theft, especially against a knowledgeable thief.

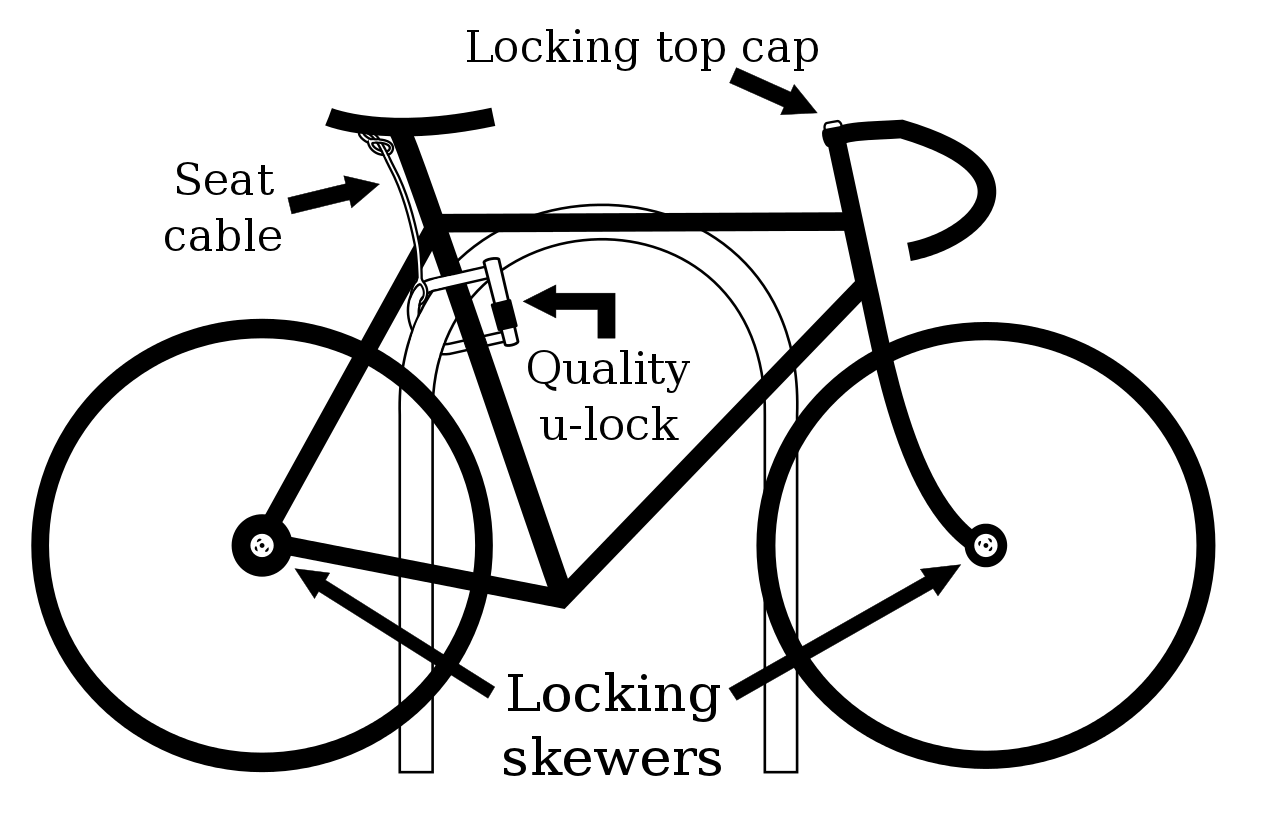

Imagine you arrive at your destination, find a spot on the bike rack, pull a small U-lock out of your back pocket, lock through the frame where a small cable hangs, and walk away. Your bike is now secure from wheel to wheel, and it took five seconds. How is this possible? Simple, efficient locking technique.

When buying a U-lock, smaller is better. The reason for this can be derived from the previous study of how thieves operate. The larger the U-lock, the easier it will be to fit a jack inside, and the larger the area for the jack to deform the U. You want the lock to be tight against the frame and the anchor; no space to adjust the lock, meaning no space to fit a jack and no space to fit a hacksaw comfortably.

The first benefit you will experience using this method is lock portability. If you have a large enough butt, you'll be able to fit one of these mini U-locks into your back pocket. If your butt isn't big enough, don't worry: As you continue to cycle, your butt will grow as you build muscle. (Kidding! Well, sort of.) However, if for some reason your butt refuses to grow to sufficient size, you can easily use included or after-market mounts to secure your lock to your bike or belt while riding. I include after-market as a suggestion here because some of the mounts included are flimsy and can scratch your paint if not installed with the utmost care and attention.

However, not all U-locks are created equal. There are really three levels of quality when it comes to U-locks. The lowest is cheap, thin steel covered in plastic, typically sold at hardware or general stores; do try to avoid these. The first level of good U-locks is high-quality, single-side-locking U-locks that are easy to find in a bike shop. These are acceptable as long as they are not too big; I use one daily. Finally, the highest quality U-locks lock on both sides of the U and typically weighs significantly more (due to its tougher steel and more complex locking systems). It is about double the price of its single-sided counterparts. The benefit of locking on both sides is extra protection against jacks. It is much easier to stretch open a lock with a jack when one end is free. Still, it's always best to have a lock that a jack cannot fit into.

"But ... but ..." you say, "How am I supposed to secure my wheels if my U-lock is so small? Do I have to buy a cable to wrap around them?." You could buy a bulky, awkward, weighty cable simply to lock your wheels, or you could buy locking skewers.

Here I must digress. Typically, bicycles come with quick-release skewers (those little twistable arms that come on your bicycle wheel that make them easy to steal). Now imagine yourself near the front of the peloton racing in Le Tour, muscles burning and the wind at your back. You suddenly hit a piece of glass or a thorn in the road. Shock sets in; thoughts of years of training lost to the fortunes. Luckily, you have a team car behind you with a replacement wheel at the ready; plus, you've taken the time to grind away the lawyers' lips from your fork to ease transitions. The time you save using your quick-release skewers gets you back in the peloton before you fall dangerously far behind. Aren't quick-release skewers great?! Wait, what you mean you don't actually cycle competitively? Changing a wheel in under three seconds isn't important to you? What the hell are lawyer's lips, anyway?!

Confused? Me too. I hate quick-release skewers. They provide zero added benefit to the average cyclist, and make bicycle wheels effortless to steal. I hypothesize that they are somehow cheaper in the manufacturing process (or something to that effect), because I don't know anyone in their right mind who prefers these theft magnets to even the simplest alternative.

If I could give people one piece of advice on making their cycling experience better, it would be this: Buy locking skewers. (Unless you have a fixed-gear, and only if they are compatible with your hubs, obviously.) These little guys are relatively inexpensive (usually only slightly more expensive than that bulky cable) and add zero weight or hassle while securing both wheels. They are not undefeatable, but only a professional thief will be able to get past them. In addition to securing the wheels, they actually make the bike less attractive if stolen, as a simple flat tire will render the bike virtually unusable. Just don't lose the key (!), or at least record the model and serial numbers to order a replacement, and keep them with your bike's serial number. (Did you record your bike's serial number in case of theft? You should.) So, I ask you ... no, I beg you: Please spring for locking skewers.

I must, in full disclosure, point out the primary downside to locking skewers. One must, to remain practical, buy a set for each bicycle. This could be an issue if one owns many bicycles, but I'm assuming that a person who can afford many bicycles can also afford the convenience of locking skewers. The price is a slight inconvenience, but one well worth the trade-off.

The other alternative is bolt-on hubs. These come standard on most single-speed, three-speed, and fixed-gear bicycles. These are significantly better than quick-release skewers, and will generally deter passersby from stealing your wheels; however, any degenerate with access to a 15mm wrench will be able to get at your wheels in under a minute. There may be a keyed nut available, made especially for locking bolt-ons, but I don't know about it. Even with a fixed-gear bicycle, however, one can still replace the front hub with one that is compatible with a skewer.

Two other areas may need attention once you've secured your frame and wheels if you live in a high-crime area: the seat and the stem. There are various methods to locking one's seat, and I will discuss four in particular: three dos and one don't. Though when discussing how to lock one's seat, there is the issue of whether the seat is worth anything to begin with. Considering the various types of seats on the market, it might not be worth the effort. If you have a cheap seat and seat post, it may suffice to merely have an Allen wrench bolt; however, if your bike comes with a quick-release seat, it should be replaced (except in the case of multiple people riding the same bike, or a folding bike, or if you decide to take your seat with you when locking your bike, etc.). This is a cost-benefit analysis. If you have a sparkling new stretched-leather saddle (with a limited-edition topographical map of a famous bike route-impressed into it17), then you must protect your investment.

First, if your seat is worth anything, I suggest you actively engage in bike-seat camouflage. This involves putting a messy-looking plastic bag over you seat when it is unattended. This serves two purposes. The first is quite obvious: to hide the quality of your saddle from the ever-untrustworthy pedestrian. Second, it protects your saddle from the elements, specifically rain, if it is a leather one. A bag may heat your saddle if you live in warmer climates, so you may prefer bags in lighter colors (e.g., white instead of black), along with allowing proper ventilation.

Always secure the seat rather than the seat post. Now, the method I prefer is using a small, but quality, after-market seat cable. They are quite thin and inexpensive, thus they provide significant safety at minimal cost. The system here is to make a slipknot through one of the rails of the seat, and attach the other end to your U-lock when you lock your bike. It is best to secure the cable (via a velcro strap) so that the locking end hangs on the left side of the seat tube. Typically, one will lock the left side of his or her bike to an anchor (so as not to disturb the drive train), and having the cable waiting on the left side will expedite this.

Now, this method can be easily broken by professional thieves, either by using simple bolt cutters or possibly by torquing the cable (though this might damage the seat). However, with proper camouflaging, it would be difficult to reason how a thief would single out this particular saddle without premeditation.

A similar approach is the chain-in-tube method. This is the most frequent practice I see on the street and I generally support the idea. A bike chain is wrapped through the seat rails and under the seat stays. It is then placed in an old bike tube of similar length (to prevent scratching the paint and rusting) and is locked into place using a chain breaker18. The tube is then either patched or sealed with strong tape, after which the seat is secure. The obvious upside of this method is that it is a cheap, easy, and permanent deterrent. The downside is that it tends to be ugly and easily defeatable by anyone with a chain-breaker. However, for moderately priced seats in relatively crime-free areas, this method is more than satisfactory.

For extreme protection, I would suggest a combination of methods. First, use a cable (or chain in tube) to provide a holdfast against someone with tools. Then, superglue an appropriately sized ball-bearing into both the bolts holding the seat into place (the bolt holding the seat tube to the frame, and the bolt holding the seat to the seat tube). To remove these ball-bearings, one must apply nail polish remover to the glue and it will eventually come loose, restoring the function to the bolts. The benefit is that any thief will have to go to great lengths (multiple implements, and a significant amount of time) to steal the seat. The downside is that it will be nearly impossible to adjust the seat if someone else needs to use the bicycle.

Another option for extreme protection is specialty security bolts. These come in a variety of shapes (five-point Allen wrench bolts, Allen wrenches with holes in the center, star screws, etc.) and can be quite expensive. Professional thieves may possess these tools, but it's certainly effective for someone who is willing to spend the money for ease of adjustment. (Just don't lose that specialty Allen wrench!)

Finally, a word of warning: There are locking skewer-style replacements for quick-release saddles. I do not endorse these, because they are designed to go on the seat post's connection to the frame, leaving the contact between the seat post and saddle unprotected.

The contacts for the other significant parts of the bike are much more difficult to protect. There is the fork, handle bars, brake levers, and stem. Fortunately, for threadless forks, there are locking-top caps. Buying a locking-top cap will lock the fork and stem into place, but will not protect the handlebars (as the pop top can still be removed). To protect threaded stems and handlebars, the ball-bearing method can be used. Though this can be cumbersome, it's really the only solution short of buying expensive specialty bolts. For brake levers, unfortunately, there is no real solution. The contacts are usually too small and delicate to use the ball-bearing method, and anyone could simply cut the cables and tear grip tape (or grips) off to remove them. I really don't have a solution for this problem; fortunately, it doesn't seem to be much of an issue as far as general bike theft is concerned.

One issue you may encounter is how to lock to certain poles or fences. Your seat or pedals may get in the way if your lock is very small. The answer lies with clever locking technique. Often, you may find yourself with only a fence post or bulky parking meters to lock to. Unfortunately, your pedals and seat may push up against fencing and prevent you from getting the frame close enough to lock with much room to spare. This problem can be alleviated by locking through your left seat-stay. Your seat stays (the smaller tubing connecting the seat post to the rear wheel) are the widest sections of your frame. They will allow your seat to be much farther from the anchor compared to locking through the front triangle. The left side is preferred because it leaves the delicate bits of the drive train untouched.

Another reason to lock here is that the seat stays generally have a much smaller circumference when compared to top tubes and seat tubes. This will provide those precious extra millimeters when attempting to lock in tight spaces. While it's a bit trickier to get the lock around the stay without molesting the rear wheel or the brake, it's worth knowing for when you find yourself in a tight locking situation.

You can still get a cable through both wheels using this method (assuming I still haven't convinced you to buy locking skewers); just make a slipknot through the front wheel and connect the other end through the rear between the wheel and into the lock. Your seat cable should stretch far enough without any problems. I've found that this method allows me to lock securely in some of the most difficult situations. Occasionally, I must search for another place to lock, but very rarely.

The late cycling authority, Sheldon Brown, popularized one specific method now advocated by many. Using his method, one locks the rim of the rear wheel at a point inside the rear triangle. The brilliance to this method is that even if the rear wheel is removed, the frame cannot be stolen because the wheel won't fit through the rear triangle. It would have to be mangled beyond all recognition to be removed, and a thief is probably not interested in damaging the second most expensive section of the bicycle.

While this method is probably adequate for most low-crime areas, there are some drawbacks. First, the front wheel must be locked by some other means; if this is the case, why not just go all the way and spring for locking skewers?

Second, while the tension of the rim may discourage a thief from hack-sawing through the rear rim, it will certainly not prevent it. There is a video of a rim being sawed through without much difficulty19. It was an old rim and the spokes were rusted, but the fact that it took so little effort should be worrisome to anyone endorsing this method.

The modified Sheldon Brown technique is worth noting. You can actually fit a mini-U-lock through the rear rim, the left-side chain stay (near the bottom bracket), and an anchor with most bicycles. This locks both the real wheel and the frame together. It's pretty tricky to get it on properly, but if you have no other options, it's worth using. It's perfect for fixed-gear bicycles when locking skewers on the rear wheel are not an option.

Though I would not advise leaving a bike out for signifiant periods of time in a high-crime area, sometimes this is not an option. This is why heavy-duty chains exist. Make sure you buy quality at a bike shop, not a hardware store. These chains are probably the best protection against theft. However, the downside is cost and weight. They are extremely heavy, often weighing over ten pounds, and usually cost more than double the price of a quality U-lock. Still, these downsides can be justified.

The best way to use a heavy-duty chain is (what I call) "point-B locking," where, instead of taking the lock from point A to point B, you just leave it at point B. In this scenario, suppose you are a bicycle commuter and cannot bring your bike into the office. Ideally, there would be an alternative, such as a commuter hub where you could store you bike during the day, but these are exceptionally rare. You can avoid the weight of the lock by leaving it at point B. Yes, just leave your heavy chain locked to whatever anchor you lock your bike to. The main concern you should have is protecting the lock from the elements (rust), but you can coat the connecting pieces in waterproof grease, and most of these locks have a piece built in that cover the keyhole for this purpose. Second, there is the issue of dogs peeing on your lock. (This could happen, but it's not really a health concern, it's just gross; I probably shouldn't have even told you about it.) Also, it is a good idea to change up your locking habits fairly frequently, since you will probably be locking there regularly. Allowing for premeditated theft is a bad idea, so expect to carry the lock around some, but this should be relatively manageable.

The other purpose for these heavy chains is if you live in an area with no good bike racks or other anchors to lock to. They are very useful for locking to unusual anchors: lampposts, fencing, scaffolding (be careful that the scaffolding is secure, though, and cannot be removed with a wrench), barred windows, even exposed pipes; just don't use them to lock to trees. These locks are an expensive and heavy hassle, so unless you live in a major city (like New York City or Chicago), I wouldn't really recommend carrying one around with you.

The last use is not recommended, but I'll include it because I figure many of you planing on locking your bikes outside overnight anyway. If you have a crappy bike, or live in an especially low-crime area, you can use one of these large chains for locking your bicycle outside overnight. Your poor bike will slowly waste away, rusting in the exposure to the rain and humidity, but it's your decision. If you have a nice bike, however, it will probably still end up being stolen and, unfortunately, you will have to add that broken (expensive) chain to your loss, too.

So, suppose we have the good, the bad, and the ugly of bike locking. If the section we just covered was the "good" section, this would be the "ugly" section. These methods will work, but I continue to scratch my head each time I see their impracticality on the street.

First, large U-locks locked through the front tire, frame, and anchor; this protects your front tire, and frame, but nothing else. Large U-locks are generally easier to break than smaller U-locks, so, here, one is actually reducing the quality of protection while also creating unnecessary bulk and weight in transport. There is no added benefit. The only logic I can find to explain this phenomenon is that large locks simply look stronger when hanging on the rack at the bike store. Otherwise, I really have no explanation for why most U-locks I see are huge.

Second, bikes scattered around my neighborhood have large, bulky cables connecting the wheels to a U-lock. Now, this is a perfectly reasonable way to lock one's bike, but for just a few more dollars, one can purchase locking skewers. Also, I often see bikes where a cable is actually locking the bike to the anchor, not the U-lock. The U-lock should always take the priority to cables in protecting the frame. Cables are much easier to break than U-locks. By anchoring the frame with cables, one is putting the bike at significantly more risk without any added benefit.

Finally, one has to consider the extra weight and bulk of carrying these cables around. They must be slung around the torso or put in a bag while riding, though they often have dirt or grease on them from their contact with the bike and the elements, which creates the the possibility of stains. Plus, they make locking much more laborious: slinging cables around, and navigating spokes and tubing. No, locking skewers are simply a much more elegant solution. I can't imagine people wanting to go riding around with all those cables hanging from their body all the time once they understand the alternatives.

Now for bad locking technique. First and foremost, check to see if your lock has been recalled. In 2004, there was a highly publicized recall of U-locks with round keys because they could be opened with the body of a common plastic pen20. Those round keys have since been replaced with their flat-key counterparts. Also, most locks come with two (or sometimes three) keys. If you've decided to get a lock on Craigslist or eBay (something I wouldn't recommend), check to make sure they have given you all the keys, as it would not be too difficult to steal a bike if one still has one of the keys to the lock.

Oh, hey, did you find that cool, off-brand U-lock for cheap at the hardware store? Well, sorry, but it's very likely a piece of junk that can be broken with a crowbar. Without even getting into the quality of the steel, you can see that the circumference of the steel sections of these locks is much smaller than higher-quality U-locks. All that plastic they use to bulk it up isn't going to do anything for you when someone decides he wants your bike. The illusion may be good for moving cheap product, but it's not helping you protect your bike.

What about that convenient cable lock your friend has for his old bike? It's a huge cable, with a key or combination lock at the ends. Unfortunately, even the higher-quality cable locks are some of the easiest to break. The contact points of the cable and the locking mechanism can be broken if the lock is torqued enough. Don't buy a cable as a primary lock; stick with solid steel.

If you have a cable lock locked together with a padlock, then you have a lock that is dangerously weak. Anyone with a bolt cutter can break it easily, and there are a lot of thieves with bolt cutters. A crowbar could probably break it; heck, you could probably break it by hacking the spring mechanism21. I am shocked by the frequency at which I see this method. It may be acceptable if your bike is worth nothing, but if you do have a decent bike, you aren't going to have it for long if you are locking like this.

Some other techniques for preventing bike theft are lifestyle choices. First, and foremost, you should write down the serial number of your bike. Yes, do it now; it should be engraved underneath your bottom bracket (the lowest point on the frame). Put down this book, go write down the serial number, take a photo of your bicycle, and make a note of any identifying characteristics (a scrape in a discrete location, a unique sticker). Keep these on file (digital or physical copies) and register it with a local or national bicycle registry if you can. Do it so that if your bike were stolen tomorrow (or perhaps removed by the authorities for some reason), you will have all the pertinent information to give to the police. Do it now ... seriously.

Another thing I would suggest is putting a small note with your name, a statement of ownership, and contact information inside both of your tires. The simplest repair that someone unfamiliar with cycling will get is a tire change. If someone were to take your bike into a shop, the mechanics will always check the inside of the tire for any sharp debris; thus, he or she will fine the note and may be able to contact you in order to recover your bike. It's an easy way to possibly recover a stolen bike and will stay there for years after a theft.

There is also the habit of storing your bicycle inside. It's best to take it inside whenever you can, especially overnight. This can be difficult if you live in a fifth-floor walk-up, but there are bikes specifically designed to be carried (cyclocross and folding bikes). Here, the quality of your bike (as far as weight is concerned) is going to matter. A 15-pound single-speed is going to be easier to carry than a 35-pound cruiser. If you have a garage, you're in luck, but consider locking your bike when it's in the garage, as many people leave their garages unlocked (or even opened), and I do have a friend who lost his bike this way.

Uglification, the process of making a shiny new bike look old and beat-up, is another way to thwart thieves before they even think to steal your bike. I already talked about camouflaging your seat; this is essentially camouflaging your entire bike. This will also make your bike easily identifiable. People often use stickers or powder coating. I've even seen specialty stickers that look like cracks or dirt, specifically designed for bicycle uglification22. You don't want to be a target, and uglification will make your bike somewhat less attractive to potential thieves. The only downside is that your bike ends up less pretty.

Consider locking up next to poorly locked bikes. This is a bit of economics; if you were a thief, and you saw a poorly locked bike next to a well-locked bike, and assuming your fence will give you the same price regardless, which bike would you steal? The answer is certainly the poorly locked bike, as it's easier to steal and will probably take less time and effort. Now, obviously there are other factors, and without proper studies, one cannot know if there are any externalities or flaws with this intuition. So while I can't endorse this method in good faith (as I don't know if it is factually better), it seems intuitive to me, and if it seems that way to you, consider it.

Finally, if you happen upon someone stealing your bike, be careful. Your first reaction should be to call the police from a safe distance. Try to get a good look a the thief and remember his height, build, attire, appearance, and any other relevant facts. This will obviously be useful to any investigation, supposing he ends up stealing your bike.

Do not fall in love with your bike. There, I said it. Okay, I realize this is sometimes impossible; but at least try not to fall in love with your bike. I only say this because many bikes will be stolen. My bike could be stolen and your bike could be stolen no matter how well we lock and protect them, and the anguish I see when I read people's stories of loss breaks my heart. I don't want to kill the romance, but in the end, it's just welded steel covered in paint. Bikes are tools. An emotional bond is wonderful, but if misfortune befalls you, try and keep it in perspective.

While security devices can be expensive, I want to try to make an argument for why they are worth the money. For new bikes, this is fairly straight forward. Typically, I would suggest spending 10 to 15 percent of the purchase cost on locks. This means if your bike cost $800, you should expect to spend between $80 and $120 on locking devices. Spending this much should allow you a high-quality U-lock, skewers, and a seat cable. Try to include this amount when deciding how much you are willing to spend on a new bicycle. Combine this with good technique, and it should keep your bike as secure as reasonably possible for almost any threat.

Now suppose you purchase a used bike for very cheap, say, $150; how can you justify spending 25 to 50 percent of the purchase cost on locks? The answer here is with replacement costs. Unless you have access to a cooperative or other bicycle nonprofit, the cost of many replacement parts are going to rival buying an entirely new bike. Replacing a rear wheel, for example, could cost anywhere from 40 to 100 percent of your purchase price (depending on the availability of parts in your area). This would essentially make the bike worthless, as though the whole bike had been stolen. Here, protecting yourself, even with lower-quality, merely decent locks, may end up saving you money in the long run. However, I don't want to overstate the protection of low-quality locks. With a cheap, old bike, it may ultimately be mere chance that decides whether or not your bike will be targeted by thieves.

There is also the option of insurance against bicycle theft. It is often included in homeowner's or renter's insurance, or added at minimal cost. This is probably one of the best ways to be reimbursed in the event of professionals targeting your bike. There are costs, however, that will be incurred even if you have insurance; there are premiums and the cost of the time it takes to replace the bike. Insurance can be an addition to proper locking technique, not a replacement.

Improper locking technique also has costs to a community. Often, when wheels or parts are stolen on the street, the owner of the bike leaves the skeleton to rust without removing it. This is incredibly antisocial. There is a limited number of bike racks on the street, and that type of negligence and laziness inhibits responsible people from accessing these public spaces. It forces many to look for racks or posts further from their destinations, and may cause them to lock to a less secure anchor. Bikes left to rot clutter the street, block pedestrians from public space, and often create unsightly eyesores. There are many legal hurdles to removing them, and it usually takes months, if not years, for a community to act. Even if you can't find any value in such a piecemeal collection of parts and frame, I assure you, if you've had parts stolen, there are probably a few quality charities in your area that will be able to use all the leftover parts to help create useful, recycled bicycles for those less fortunate in your community.

So, I hope I have convinced you that bicycle security is more than just buying a lock. It's unfortunate that theft is so prevalent, but I hypothesize that with proper technique, it would be nearly eliminated. I might be wrong, though. Perhaps better locking would simply lead to better thieves; perhaps those that lock their bikes poorly do us the greatest favor by lowering thieves' expectations to the point where they are unwilling to buy, or at least deterred from buying, the tools that would put properly secured bikes at risk. No matter; it's not as if that is going to change any time soon. Even in the bicycling capitals of, say, Amsterdam, Portland, or even Copenhagen, poorly locked bikes are ubiquitous. Thus, to sum up, I started with the question, "What is the best way to get my bike stolen?" The answer is to have it stolen by a professional. Otherwise, I would not have put forth a decent effort protecting it. I am under no illusion that bikes can be secured from all threats; perhaps my bike will, one day, be the victim of an angle grinder, or perhaps some enterprising young thief will develop an ingenious and previously unknown method of dislodging a bicycle from its bulwarks, but I am quite certain that my bike will not be the victim of some halfwit with a crowbar. As for the bicycle thieves out there, I have nothing but distain and pity for them.