"Do they ride bicycles in America?" Aymo asked.

"They used to."

"Here is a great thing," Aymo said. "A bicycle is a splendid thing."

"I wish to Christ we had bicycles," Bonello said. "I'm no walker."

-Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms, 1929 i

Who needs a book about bicycling? Actually, many people could benefit from one, though many of them don't even realize it. Buying and using a bicycle effectively is often counterintuitive. It's just a fact. Is locking your front wheel to your frame the best way to lock it? Nope. Do you imagine commuting to work on the same roads you take when you drive? Probably best to avoid those. Who would know what type of steel is best suited to your needs? However, all this is likely to determine whether someone loves a bike or hates it. You see, if you are relatively new to cycling, you probably aren't aware of many of the facets of bicycle culture. This, however, does not mean you must become some hoity-toity bike snob. It's just that, over the last 60 years, while America had its love affair with automobiles, other parts of the world were still nurturing large cycling cultures. Our country has, thus, lost much of its cycling heritage. Don't worry, though! It's all super easy to understand. Unfortunately, bikes, while simple, don't come with instructions. So, consider this book a general introduction to bicycling, but also an introduction to bike culture.

When one of my close friends came to visit me a few years ago, we rode bikes all around the city. He enjoyed it so much, he decided to buy a bike when he got home. He eventually told me what he was looking at and I helped him pick the bike that I thought had the best value. After a few initial rides, the bike was hung on the wall, remained unused for over a year, and was eventually sold. I was a little unsettled when I learned this. I came to realize that cycling is often more about your current living situation than about simply owning a bike. One of the main reasons he didn't use his bike is that getting it up and down the narrow stairs in his apartment wasn't easy. He was excited about the experience he'd had with me, but it really didn't translate to his environment. There are lots of different types of bikes! Some are more appropriate to different lifestyles than others. (I think a full-size folding bike would have suited him much better; I regret not suggesting it at the time.) This variety is something worth knowing if you are considering getting a bike for yourself, which is why I cover it thoroughly in Chapter 1.

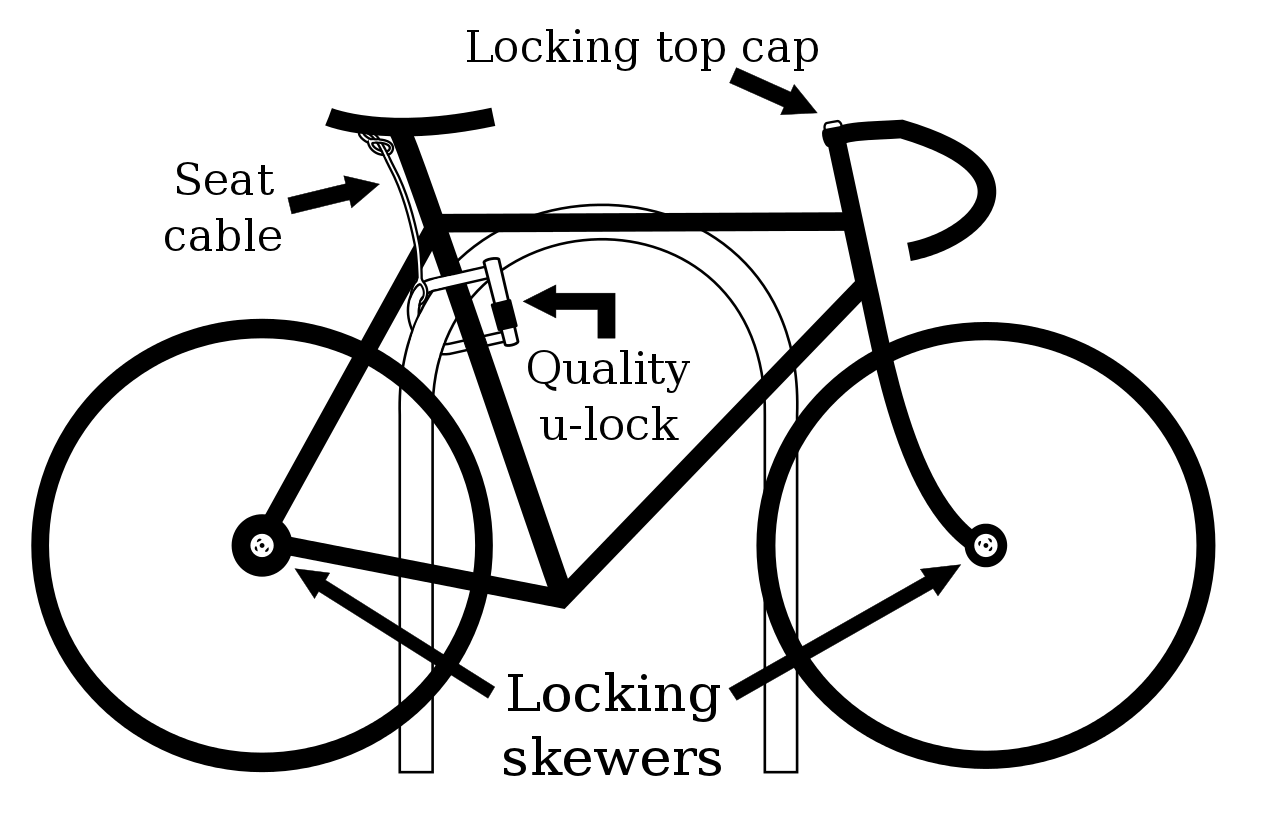

Again, bicycles don't come with manuals. Riding your bike in the city isn't dangerous, but you really should know what you are doing. In Chapter 3, I cover some general guidelines about getting through trouble spots in traffic. Knowing what to expect on the road is helpful, but knowing what to do when locking up is important too. I cover bicycle security extensively in Chapter 4. You see, most people just don't lock their bikes properly. This is one of the reasons why bike theft is so rampant. It doesn't have to be this way! Here, I've highlighted the important bits so you can just skim through them if you live in a relatively safe neighborhood and aren't concerned about the details. Proper locking technique is something many cyclists never learn, but they certainly should. It can be quick, simple, and lightweight when you do it right, but will be clunky, heavy, and time-consuming when you do it wrong.

Even with proper locking technique, however, you can also find yourself in trouble if some part of your bike is damaged. This is why I included a section on general maintenance in Chapter 5. Whether it's comfort or performance, the condition of your bike will affect whether you want to ride or not. A little bit of waterproof grease and chain lube goes a long way, but wear is going to eventually happen, and you should be prepared. Worrying about flats is something that won't concern you when you know how to fix them in a couple minutes. When a common problem comes up, knowing what you can adjust yourself versus what needs to be done by a professional is quite valuable. It saves both time and money.

This book is for my written with close friends in mind. If the tone is informal or flippant, this is why. My inclination to write a book came as a way to help more of my friends with their bikes. As a result of the current increase of bicycling culture in the United States, a few of my friends have been interested in using a bike as transportation in the city. I started by sharing my experience, and gave advice whenever they asked. Surprisingly though, those "few" friends have become "many" of my friends (and family), more than I ever thought would ask. I eventually decided it would be better if I just wrote down this advice so people could pass the tips to each of their friends in turn.

I've also been concerned about some of the negative reactions that my friends have had when they started cycling. Many of them are shocked when they borrow one of my bikes. Their butt no longer hurts, and the bike is "so light." I know that peoples' first reactions to the bikes they buy can affect the way they view cycling for the rest of their life. Unfortunately, I haven't come across any field guides for buying a non-crap bike. So I made that my theme: How to make cycling never suck. I enjoy cycling, and I want others to as well. No matter what your experiences in the past, a bike can (and should) be comfortable, convenient, and fun.

While I am quite sure that everything in this book is entirely noncontroversial, the fact remains that some of the ideas I suggest may not be endorsed by certain bicycle manufacturers or may not be legal in your area. I ride my bicycle in exactly the way I present throughout this book. I believe it is safe, and encourage it. However, this book is presented as is, without any warranties (implied or otherwise) regarding its accuracy; you need to be aware of how your particular bicycle will behave with any change or modification, so I implore you to find and consult with a competent bicycle mechanic whom you trust, who is knowledgable about the make of your bike and its components. You should also be aware of any and all local, state, and federal laws, and abide by them. I want to give as much advice as I can, but whatever decisions you make about your bicycle are your own, and you make them at your own risk. I certainly hope you are not dissuaded, though. While certain things may not be applicable to you, the vast majority of this book should be.

"Long ago, Ben Graham taught me that 'Price is what you pay; value is what you get.'"

-Warren Buffett1

There are two ways people approach buying a bike. Some want something that is "cheap," others want something that is "nice." Both approaches are totally cool. Unfortunately, what "cheap" and "nice" mean to various people is wildly different. I tend to categorize these two perspectives into two distinct groups: those who want something disposable, and those who want something to last. I use the term "disposable" because some people seek out high-quality, yet very inexpensive, bikes from Craigslist to fix up and take care of, while others will often buy new (and expensive) bikes, but treat them poorly until they have wasted away, at which point they buy a new bike. These two methods involve different expectations, and will affect the type and quality of the bike to purchase. To maximize your value with either method, you will need to know some things about buying a bike. Since I'll be referring to prices that can fluctuate rapidly and can differ in different areas of the country, I want to point out that I'll be referring to prices from 2011 in U.S. dollars, and all prices are only estimates.

When first purchasing a bike, people usually have a general idea of what they want; however, there are many more types of bikes than most people know about. How can people know they don't want something they don't know about? There are enough types of bike such that I feel comfortable saying that if someone wants a bike for some particular use and is willing to pay for it, there is a bike perfectly suited to every need. I'll go through a reasonably in-depth list of the types of bikes out there, as most people aren't even aware that their ideal bike is waiting for them.

I'll start with those who want a cheap, disposable bike. Typically, this person simply isn't ready to commit to cycling; he or she just wants to try it out. Here, I want to make it clear: Bikes are not toys. They are vehicles. If you walk into a bike shop and tell someone that you just want something that does x, y, and z and costs less than $100, the response may be a bit awkward. If the shop is especially helpful, it will probably tell you to try Craigslist or that it's just not possible. There is often a real disconnect between how bicycles are viewed by an avid cyclist and by a layperson; this can make for some uncomfortable conversations during the initial sticker shock, but don't be dissuaded by a rude bike-shop employee. I'm here to help!

Essentially, the cheapest solution is a high-tensile strength steel single-speed (which is a bike with only one gear) or a used bike, and your best vendors will probably be Bikes Direct or Craigslist (respectively). If you live in a large enough city, you will also have the option of a bicycle cooperative. If there is a co-op in your city (you should check2), I highly recommend this route, as you can typically donate money (read: "buy") or volunteer your time in exchange for a solid used bike. Unfortunately, cooperatives are exceedingly rare, though they will only become more common if the demographic of bicycle commuters continues to grow. If you can get to a co-op, do it. It can help you to buy and maintain your bike at essentially no cost.

If you decide to shop on Craigslist, you should expect some immediate maintenance, unless you buy a bicycle that has been well taken care of or rarely used. If you are handy with the Internet and a 15-mm wrench, you should be in good shape. At a bike shop, however, even this minor maintenance may cost more than you paid for the bike. So be very careful with exceedingly inexpensive bikes. Later, I'll discuss some general guidelines and red flags to look for when buying used bikes, but if you really have no idea what you're doing, you should probably only look at single speeds, as they are easier to evaluate.

Now, I'm going to assume that you probably won't practice proper storage (no offense), which also points to buying a single-speed, as even when treated harshly, they tend to operate surprisingly well. The only real downside is if you live in a particularly hilly area, at which point gears start to make more sense. The real irony, unfortunately, is that cheap gear-shifting components tend to rust and wear rapidly. Thus, even if the bike is rarely used, when stored outside, it will still stay in better condition if it is a single-speed.

So, if you want to save yourself the time searching Craigslist takes, just go to Bikes Direct3 and navigate to the "single-speed/fixed-gear/track" section. (It is usually hidden as a subsection of the "road" section. Don't ask me why.) Here you can pick out the cheapest, lightest, and probably best overall value bike they have. It'll run about $300 for a chromoly-steel-frame bike (check the specs section to see what metal the frame and fork are made of). Without getting into the details, chromoly steel is a better alloy; you could buy high-tensile steel if you really don't care about the weight of your bike, though I can assure you that you will prefer chromoly. If you get a single-speed via this method, they will ship you a really decent bike, that will last, for cheap (yes, $300 is cheap for a quality, new bicycle). You will have to assemble it, but they come with simple instructions that anyone with a little patience and a tube of waterproof grease can follow. So browse around until you find something you like.

Finally, please, I beg you, do not buy a bike at a big-box retailer; they will sell you what is known as a "bike-shaped object." Even if it is new, it will probably start breaking down within a few weeks. Seriously, I'm not kidding.

If you aren't constrained by spending the absolute minimum, your choices are significantly greater. Here, I will go into some very specific styles of bikes, but none of these are hard-and-fast distinctions. There can be variations of each style; for example, a hard-tail mountain bike can be turned into more of a city bike if some subtle changes are made to the tires and handlebars. So while I will lay out many different styles, don't think you will be pigeonholed. My favorite variation is the cyclocross bike with city tires and a touring seat; I ride one and it is a remarkably nimble commuter.

Now before I start talking about different styles of bikes, I want to address a common misconception about step-through frames. There are bicycles designed for women (bicycles whose geometry is subtly adjusted to better suit female proportions), but this has nothing to do with step-through frames. Yes, many women may prefer the extra room because it makes it easier to ride in skirts and dresses, but without a skirt guard, these can be downright dangerous. Step-through frames offer a huge benefit when mounting and dismounting a bicycle loaded with a briefcase or a bag of groceries. The main reason a full-diamond frame is used is that that is the lightest and strongest form a bicycle can take. They are cheaper to manufacture. The idea that step-through frames are only for women is simply a myth. Consider them.

To continue the theme of bicycles for simple transportation, I start with city bikes, or urban bikes, because they are the ideal type of bike for getting around a neighborhood. There are many different styles, but most revolve around the theme of an upright riding position, swooped-back, comfortable handlebars, large saddles, and wide tires. Typically made of steel, they allow for a comfortable ride and will last a lifetime. Their features are ideal for many reasons: The handlebars provide plenty of room for baskets, racks, or headlights; the large saddles provide more comfort for casual riding; and the wider tires reduce PSI, which means they don't need to be re-inflated very often. The three most distinctive city bikes (in my opinion) are the Dutch Opa/Oma, the English three-speed, and the (often modified) classic ten-speed.

The Dutch city bike is, arguably, the most iconic, utilitarian bicycle. Its most recognizable feature is an integrated skirt guard, fender, and taillight. Often they will also have front and rear racks, as they are used as utility bikes in the Netherlands for everything from light shopping to serious cargo. The Oma (step-through version) is especially recognizable for its long, downward curving and step-through top tube, often reinforced to the down-tube. They are traditionally black, often with pale tires.

English three-speeds are quite similar to Dutch bikes. They were a hallmark of cycling, produced in England by companies such as Raleigh. These bikes have similar geometry to Dutch bikes, but the most notable differences are that the step-through frames are much more angular than their Dutch counterparts, they frequently come in earth tones rather than traditional black, and they typically lack a skirt guard. Their main feature is a three-speed internal transmission. This is useful for many reasons: It allows for a chain guard, can change gears while stopped (very useful at red lights), and does not require a delicate derailleur. Though the glory days of the English three-speed have come and gone, its style still abounds, especially with smaller bike manufacturers.

The classic ten-speed bicycle was prolific during the 1970s, and you can still find many of them on Craigslist today. Notable manufacturers are Peugeot, Mercier, Univega, and Nishiki. While technically these were road bikes, they have made a resurgence in America as city bikes, due to their easy conversion to single-speeds and their lasting quality. Buying a different set of handlebars is inexpensive, thus changing the riding position on an old ten-speed is very easy to do, especially since the shifters are typically mounted on the down tube, or stem. If the bike is converted to a single-speed (kits can be purchased for around $30), the shifters can be altogether removed.

Cruisers should also be considered as city bikes. These bikes are notable for their curving frames and fat tires. They often weigh more than their angular counterparts, but are perfectly useful in relatively flat terrain.

I want to point out that this is not an exhaustive list of city bikes by any means. There are also Italian, German, Scandinavian, Chinese, and Japanese city bikes, each with subtly different looks and features. Remember, these are only styles; you can get most of them from an American manufacturers. If you have the time and energy, I'd encourage you to scour the Internet to find the look that suits you best.

Road bikes are generally the standard bike people think of when using the term "bicycle." The idea of a road bike, however, is often far from the reality of the modern technology involved. While they can be affordable, they are performance bikes with price ranges that peak in the tens of thousands. They are often made of carbon fiber, but the lower-end models can be aluminum or steel. There are many different styles, from ultra-fast time-trial bikes to the near-cyclocross versions designed for the Paris-Roubeux race. If you want a bike for performance, you can get lots of help finding exactly what you want at your local bike shop or from your cycling community.

Touring bikes are also a type of road bicycle, though they are specifically designed for long travel. They have geometry for distances and eyelets for racks to store luggage. You can certainly tour your state, if not the entire country, on one of these bicycles. Tourers can ride 50 miles a day or more and still have time to see all the things that a cross-country journey entails. Touring bikes are, in large part, known for their comfort, especially their leather saddles, about which I'll go into more detail later.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the mountain bike became ubiquitous. While still technically a specialty bike, they are frequently converted into city bikes. One of the main issues you will face looking at these bikes is suspension. There are styles with front, rear, and full suspension, or even zero suspension. Mountain bikes are common, but very diverse. Bike shops are great resources for learning about the extensive varieties. Old mountain bikes are common on Craigslist, and often very cheap (especially hardtails from the '90s), so they can be a very good option if you are trying to save money on a quality bike.

Track bikes have had a dramatic return to fashion in the past decade. They are typically fixed-gear, which means that you can't coast. The rear cog is locked and spins with the rear wheel. While this may sound counterintuitive or unpleasant, I can assure you that fixed-gear bicycles are quite pleasant to ride after getting used to the different style of pedaling and adding brakes. Track-bike frames, however, are not defined by the fixed gear, but by their very steep, tight geometry that keeps the rider in a full-prone position. They traditionally do not come with brakes because they are designed for racing on a velodrome. They are performance bikes made for sprinting with full aerodynamics. The casual rider may be very unhappy on a track frame because of its geometry. However, not all bikes advertised as track bikes are actually made for the velodrome. Since their recent rise in fashion, many manufacturers are producing "track" bikes with much more relaxed geometry, often with brakes and in single-speed varieties. One can now get "flip-flop" hubs that allow the rider to ride either fixed- or free-wheel, depending on which side of the hub he or she is using. You can even buy "track" bikes with step-through frames (called "mixtes"), which is almost nonsensical, as a step-through frame would be inefficient in a velodrome. So, because of this current evolution, "track" bikes can be purchased very inexpensively and repurposed for city riding, which is probably a good thing for the cycling community, even if it bothers the taxonomists.

The term "hybrid" is a bit vague; while it technically means some hybrid of two styles of bicycle, generally, when you are asking for a hybrid bicycle you will be directed to either cyclocross bicycles or "hybrids" (which is a style in itself). The style called "hybrid" has become associated with a class of bicycles that is sort of similar to city bikes, but typically have mountain-bike components. There are other types of hybrid variations of bicycles, but these are too extensive for our purposes here.

I'll start with cyclocross bicycles. Cyclocross is a sport popular in Belgium that combines road-racing with riding on muddy trails and leaping off a bike to climb steep hills and jump barriers. It is one of the most dynamic sports in cycling culture, and necessitates a style of bicycle that is part road-racer, part off-road performer. The cyclocross (or "cross") bike is a light but reinforced aerodynamic bike, with wider-than-normal drop bars for better control in the mud; the shifting cables are re-routed so it is easier to carry, and it has knobby but still relatively thin tires. Cyclocross bikes can be found both in geared and single-speed/fixed-gear varieties.

I am particularly fond of the use of cyclocross bikes in urban environments for many reasons. First, they are performance bicycles; as such, they are generally fast and relatively light. Second, they are designed to be carried; this is more useful than you would imagine, especially if your home or workplace requires you to carry your bike up stairs. Next, they are designed for both the road and path; the knobby, slightly wider tires and wider handlebars provide significantly better control for those times when you need to travel on dirt. Plus, they are strong enough to endure the punishment of city riding (jumping curbs, potholes, gravel, etc).

"Hybrids," on the other hand, are a type of bicycle at the other end of the spectrum. They are more of a hybrid between city and mountain bikes. Typically, they have very relaxed geometry and put the rider in a totally upright position. They usually come with mountain-bike components, and, unless they are high-end, are often very heavy. I've never been much of a fan of these, as I see them as flawed versions of city bikes, but I don't want to be too harsh as this is a matter of taste. If you like the look and feel of a hybrid bicycle, you can certainly find very high-quality versions of them.

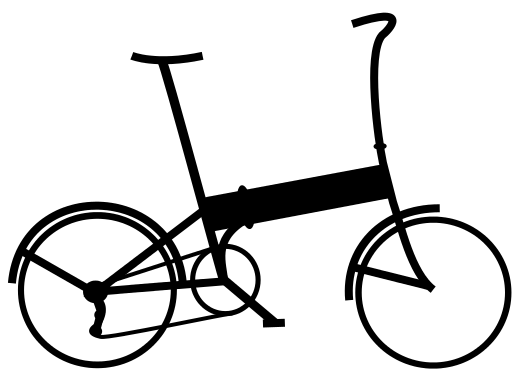

Folding bikes are fairly straightforward; they are bikes that can be collapsed or somehow made smaller for easy portage. While this industry is growing rapidly and their distinctions are immense, there are three main types of folding bikes: small wheel, full wheel, and split-frame folding bikes. Due to their engineering, they tend to be slightly heavier and can be expensive, but there are very affordable models available.

Small-wheeled folding bikes are the most noticeable. While many of them are marvels of engineering, they are generally regarded as visually unappealing (I don't share this view). The better-known brands are unique for their specific features, such as Brompton's super compact profile and Strida's long and slender fold. It should be noted that these bicycles, despite their appearance, ride almost exactly like a normal bike does, though the steering can be a bit tighter. The benefits of these bikes are obvious: portability and storage. Narrow staircases are no problem with folding bikes, so they are very beneficial for highly urban environments. With a small-wheeled folding bike, one often doesn't even need a lock, as the bicycles are allowed inside most shops and offices. They can be stored in a coat closet or in the trunk of a car, and they are almost always allowed on commuter rail. The smallest ones can even be brought onto airplanes as regular checked baggage.

Full-wheel models are much less noticeable than their smaller-wheeled counterparts. Chances are, if you live in a large city, you've probably seen quite a few and simply not realized it. While these can also be used for travel, the main uses for these bikes are getting in and out of buildings and ease in storage. The main benefit of the full wheel is that it is, essentially, indistinguishable from a normal bicycle in its ride. It is simply a bike that happens to fold up.

Split-frame folding bikes are bikes that are cut along their tubing, after which clamps are welded on that can hold the bike together. This allows the cyclist significantly greater ease in travel. Calling them "folding bikes" is slightly incorrect, as they merely are able to be separate into two pieces (they don't actually fold). Since this is often an after-market procedure, the cost and benefits can vary. They are usually only for people who are frequent tourers and are very particular about what they ride. Still, they're worth knowing about in case you have a bike you love and you really want to chop it in half.

Cargo bikes are arguably the most interesting types of bikes that exist. Since they are designed for particular purposes, the number and types of designs are always changing. Some cultures have traditional types of cargo bikes (notably Denmark), but bike companies are sprouting up around America that manufacture many of the best types of cargos from around the world. These bikes are not necessarily expensive, but the nicer, more interesting varieties are quite expensive, as they are generally purchased by businesses for the purpose of moving freight.

The first type of cargo bike is simply a fully equipped bicycle. It will have many of the following: front rack, rear rack, basket, panniers (rack mounting bags), and/or a trailer. These types of bicycles are perfect for shopping and are relatively inexpensive (since they are often just a modification of a regular bicycle). While one may first think that all these gadgets might be ugly, if one has a taste for design, beautiful racks and baskets aren't too hard to find.

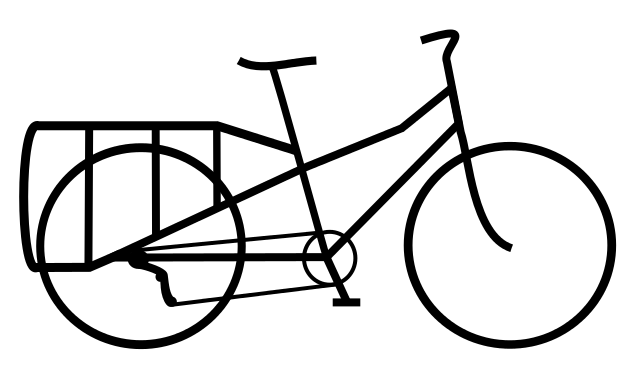

Long-tail bikes, or long bikes, are excellent cargo bikes. This type of bicycle has and extended rear rack and moves the rear wheel significantly farther behind the seat. This provides a large platform for cargo and extended panniers. The rear wheel's position provides added support to the cargo. The primary benefit of this style of cargo bike is that the steering and control stays quite similar to that of a normal bicycle. The other benefit is the cost. Xtracycle sells conversion kits (named FreeRadical)4 that will turn your bicycle into a long-tail bike for as little as $335.

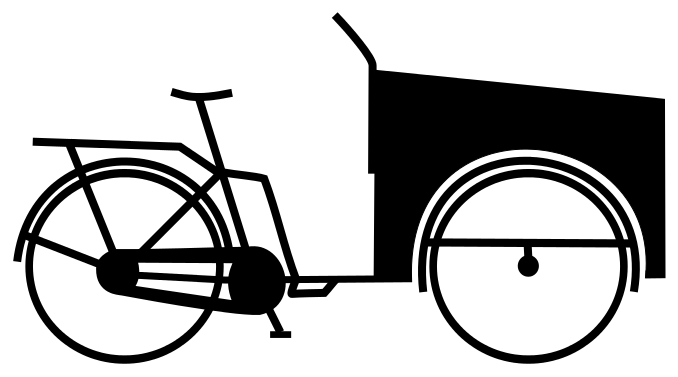

There are two main types of traditional Danish cargo bikes. The first is a three-wheeled cycle; the front two wheels support a very large container. They can also be insulated for cold storage (think: ice cream vendors) or for warm storage, and are effective for business-owners hauling bags of goods across town. While these cargo bikes are large (the front boxes can be as large as shopping carts), they are very quick.

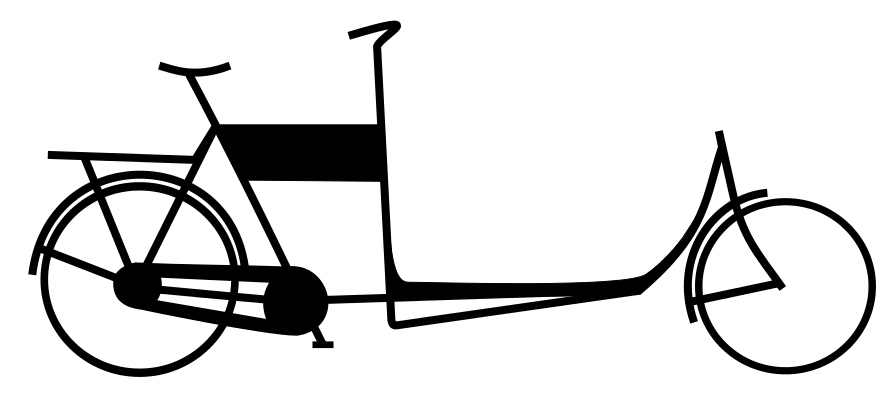

The second type of Danish cargo bike is the flatbed. This true two-wheeled bicycle has a long flatbed between the rider and the smaller front wheel. It is designed to hold enormous amounts of cargo. If you can secure it to the flatbed, you can probably haul it. The rider sits upright behind the goods and rides it like a normal bicycle, unlike its three-wheeled counterparts. They may take a bit of getting used to, but can be are very fast and quite agile.

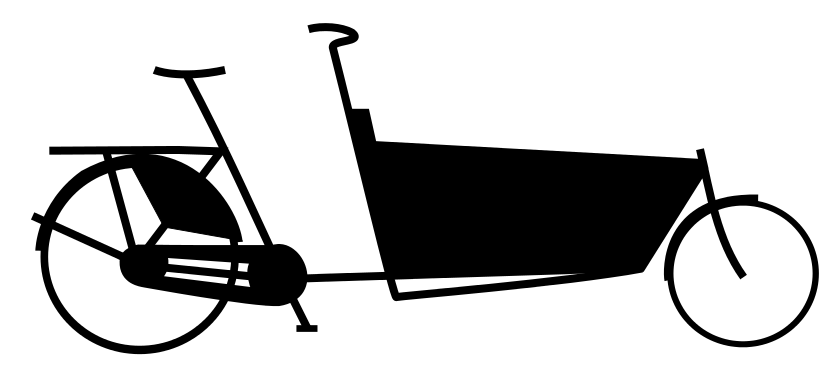

Similar to the flatbed, the Dutch bakfiets, or box bike, has a box- or wheelbarrow-shaped container where the flatbed would be. These icons of Amsterdam are frequently seen with two or three small children being cycled by their mother or father to the shops or parks. The real benefit of the box bike is its aesthetic appeal; they are beautiful, while staying inherently practical.

Finally, the only truly ugly cargo bicycle is the modern American delivery bicycle. However, what it lacks in beauty, it makes up in ability. Typically, it is some old or stolen mountain bike, a slapdash Frankenbike (a bike assembled from a myriad of random parts from other bikes), or, on occasion, an electric hybrid; the shopkeepers or deliverymen will then modify the front or back racks to have huge baskets that can carry dozens of orders around a city. I must say, while I don't really care for them, one has to admire the ingenuity of the deliveryman who pieced together one of these utilitarian monstrosities.

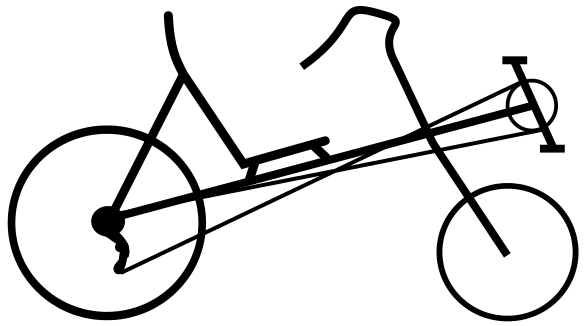

Recumbent bicycles are bicycles that place the rider's feet in front of his or her torso. These are, apparently, more difficult to learn to ride. The have some characteristics that are preferable to standard, prone bicycles. Primarily, they put the rider in a more aerodynamic position. They allow the cyclist to press against the frame of the bicycle to exert more power from each pedal stroke. Lastly, they have a real seat, instead of a saddle, which arguably provides a more comfortable ride.

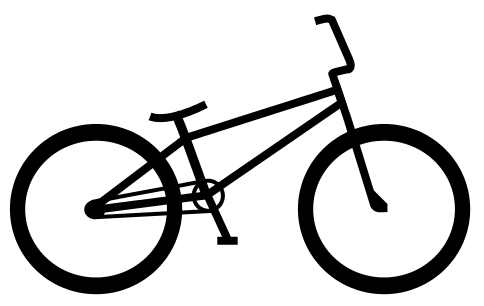

The last bikes I want to talk about are all unique; they are BMX, trials, tall bikes, and swing bikes. BMX should be familiar to most people as they were very popular in the 1980s. They have a very low center of gravity and are used in dirt jumping and other types of "extreme" cycling (I hate that term but have no other way to refer to it). So if that is your thing, you should check them out.

Trials is a type of cycling that is basically defined by it being very difficult. Essentially, it challenges the rider to get over impossibly difficult objects without getting off the bike. Trials bikes usually have very low centers of gravity and step-through frames for better balance. If you have a chance to watch some videos of trials cyclists, you should; it's some of the most impressive bicycle riding that exists.

Tall bikes and swing bikes are not produced by any companies for legal reasons, but if you know a welder, you can make yourself one. Tall bikes are made from two frames welded on top of one another, generally with some supports welded on as well. These are modern incarnations of a lamplighter bikes from the era before the lightbulb. They are very fun to ride, putting you up above even large automobiles. Obviously, the downside to them is mounting and dismounting (which can be learned, but is quite difficult at first). For this reason, they tend to be fixed-gear bicycles, as this allows the rider to track stand (a method by which a cyclist can stay upright on a fixed-gear bicycle by rolling subtly back and forth).

Swing bikes are bicycles whose frames have hinges at the handlebars and at the seat. This allows the front wheel to move independently from the rear. I've never ridden one of these, but they appear to be a good time, assuming they're not too tricky to learn. Both tall bikes and swing bikes are very rare to see in public, but if you get a chance, each is quite remarkable.

Bicycles' subtle differences are usually very difficult to notice when shopping for one. Some affect the performance of the bike while others are aesthetic. I briefly want to go over what you will encounter in a basic, starter bicycle: steel, wheels, stems, lugs, and suspension.

First, there is the type of steel used in the frame. While you might be purchasing an aluminum or carbon-fiber bicycle, most intro-level bicycles are made of one of two types of steel: high-tensile (hi-tens) steel or chromoly (CRMO) steel. High-tensile steel is generally considered the lower quality of the two alloys. It is significantly heavier and rusts more readily. However, high-tensile steel's main benefit is that it is significantly cheaper. If you live in a generally flat city and don't see yourself ever needing to carry your bike, then you may not notice the difference. Chromoly steel is light and rust-resistant; this steel will allow a decently maintained bicycle to last a lifetime. It's just better, so make sure you check the specs for this.

Wheel size also varies. The two primary types of wheels are 26-inch and 700C. These sizes are meant to represent the diameter of the tire, 26 inches and 700mm, respectively, but the actual measurements of these wheels can vary wildly, so always consult your bike mechanic before purchasing new tires for your wheels. Typically, 26-inch wheels are for mountain bikes, while 700C are for the road, though there is significant variation. Many touring bikes have 26-inch wheels, and some mountain bikes have wider wheels somewhat equivalent to 700C, called "29ers." Tire widths are still variable within wheel sizes, so remember that buying a road bike doesn't means you need super-narrow tires, and that mountain bikes' wheels can be repurposed for the road. This choice of wheel size, however, is probably moot for most new-bike purchases, as most frames will only fit one type of wheel, but be aware of the wheel size when buying a used bike or any after-market components.

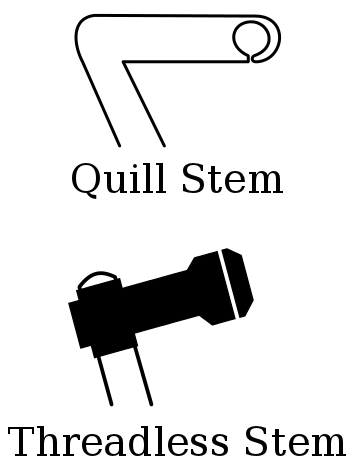

There are also two main types of stems to choose from. The stem is what connects your handlebars to your fork. Traditionally, stems were all quill stems (sometimes called threaded stems), but due to changes to bicycle design, there are also threadless stems. Each type of stem is specific to a type of fork. There are adapters, but it's not very practical to try and switch between the two. Quill stems usually have an aesthetic "7" shape and connect to handlebars via a pinch bolt. Threadless stems are often preferred because they typically have a "pop top" (also called a pillow block) connection to the handlebars. Stems with a pinch bolt require the cyclist to feed the handlebars snugly through the stem, after which the pinch bolt is tightened to hold the bars in place. This requires the cyclist to remove everything from the handlebars when removing them. A pop top has a faceplate that simply unscrews, allowing extremely easy access to the handlebars. If you plan on swapping your handlebars with any regularity, then a pop top is indispensable.

Lugs are also a unique feature of a bike. While modern bicycles' tubing is usually welded directly, lugs that connect tubing are commonly found on older or higher-end steel bicycles. Lugs these days are often intricate, beautiful accent pieces on handmade bicycles. While they may be obsolescent, some in the cycling community are still passionate about the aesthetic and functional value of lugs. For those who want that vintage bicycle look, a lugged frame is an absolute requirement.

Finally, there is suspension. Bicycle suspension comes in many variations, but the primary forms you will encounter are fork suspension, rear suspension, and occasionally, saddle suspension. Frame suspension is generally geared toward performance mountain biking. It's often very sophisticated and can be quite expensive. For most urban environments, anything beyond saddle suspension is probably superfluous. Just understand that there is a trade-off between mechanical efficiency and impact dampening. If you live in an area with cobblestones, excessive potholes, or rough trails, it might be worthwhile, but you will be losing valuable energy with every push of the pedals on flat pavement. For all intents and purposes here, buying a quality saddle and adjusting tire pressure will do more for your overall comfort than expensive frame-suspension systems.

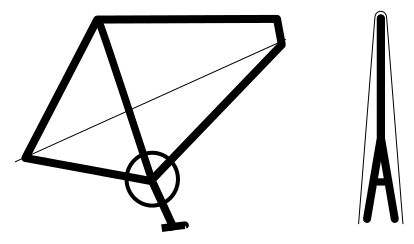

A bicycle's geometry is going to affect how it fits you. You can get more aggressive geometry, which will put you in an aerodynamic position, or you can have more of an upright, relaxed geometry. Regardless of which type of geometry you choose, the bicycle needs to fit. A bike's size should reflect the length of the seat tube, in centimeters, from the center of the weld at the top tube to the center of the bottom bracket; unfortunately, this is rarely the case. Actually, many bike sizes are a measurement of the line between the center of the top and seat tube. Thus, bike fit can be counterintuitive, so it's a good idea to get some help from your mechanic. In addition, I tend to be of the school that thinks top-tube measurement is far more important than seat-tube length when sizing a bike, but top-tube length is not usually a measurement you can get without bringing a tape measure to the store with you.

You can always get fit at a high-end bicycle shop before choosing a bike. A fitting is not just you standing over a bike while the employee nods and says, "Looks good." There will be a machine in the shop that is designed for finding your ideal fit, measured to the millimeter. While this may be impractical for most people, it's an option that does exist, especially if one is going to buy an expensive or custom bike.

Without a machine, the best way to size a bike is to test-ride it. Adjust the saddle to the appropriate height (this is discussed more later, but try to get the seat high enough that you can comfortably pedal with your heels and forward enough that your knee is over the ball of your foot on your downstroke), make sure the bike is safe to ride, and take it out for a short distance. What you should be looking for is how the bike fits your arms and torso. Essentially, if the bike is too big, your torso will feel stretched out and you will feel too much pressure on your wrists. If the frame is too small, your torso will feel bunched up and your butt will feel too much pressure. If the bike is in the right range, you torso should feel comfortable and your weight will be distributed primarily on your legs. Don't worry, though, it doesn't have to fit you exactly; adjustments or different stems allow the handlebars to vary in position. You just want to make sure your bike size is within a good range.

Whether or not to have a derailleur, or derailer (the word just means "thing that causes derailment," but in French), is one of the most important decisions one makes when purchasing a bicycle. Unsurprisingly, some people are quite opinionated about whether or not to have gears. Since the recent rise of the fixed-gear bike and single-speed conversions, a good-spirited rivalry has opened in the bike community. Internal transmissions are the proverbial Switzerland of the two sides, since they have the elements of both. Nevertheless, there are benefits and costs to each.

The choice is heavily dependent on your local topography. Take three American cities: the relatively flat grid of New York City, the occasional gentle hills of Austin, and the (figurative) alpine cliffs of San Francisco. The only need for gearing in New York is the occasional bridge and slight grade; a single-speed will suit anyone who is physically fit, though there may be some soreness when acclimating. An alternative is a three-speed, internal or otherwise, for a little help on the bridges, but this isn't really necessary in Manhattan. Austin can really only be navigated easily with a three-speed at a minimum, unless one is extremely fit. While many Austinites ride the city on fixed-gear and single-speed bicycles, the west side of the city is simply too hilly to negotiate without some gearing. For San Francisco, I would suggest a wide range of gears. Ironically, however, San Francisco has a very large fixed-gear culture; probably because much of San Francisco can be negotiated without directly encountering the massive hills. There seems to be a culture of an altering of routes to suit the cyclist, rather than choosing a bicycle to suit the map. Other than topography, however, the decision between which style to go with is fairly straightforward.

The main benefit of a single-speed is simplicity. A fixed-gear or single-speed drive train is relatively indestructible. Even with enormous wear and tear, the entire unit can be replaced, easily, for under $100. Weight is another benefit. A single-speed drive train is (to my knowledge) the lightest drive train possible; it is also mostly silent. The downside, obviously, is that there is only one gear; however, a consolation is that, depending on the area where you live, you can adjust the gear ratio to suit the environment. Typically, this ratio is measured by the number of teeth on the front chain ring divided by the number of teeth on the rear cog (for example, I generally ride a 46/17 when in Austin, though a 46/22 is probably more suitable for the hills); however, this measurement is somewhat insufficient. The length of your cranks will affect the amount of effort it takes to pedal your bicycle (the technical measurement is inch-pounds, but this is a bit too advanced for our purposes). Anyway, you'll probably want to ask people in your community, or at your bike shop, if you don't know what ratio to use.

Derailleurs were an advanced technology when they were introduced to the cycling community. The benefits are obvious; with multiple gears, one can adjust one's cadence (the rate at which a person pedals) to suit the grade on any hill. Derailleurs are often misused, though, and abused due to negligence. There are always fewer usable gearings than advertised (e.g., an "18-speed" bicycle probably has 12 usable gears, and a few of those probably overlap). The reason is that the cyclist should keep the chain in a reasonably straight line between the front and rear chain rings. This means that when the inside of the front chain ring is used (typically the smallest ring in front), the chain should be shifted to the inside of the rear cassette as well (typically the largest ring in back), and vice versa. The idea is to keep the chainline relatively straight. If this isn't done, the chain is stretched sideways and can damage the cassette.

The disadvantages of derailleurs, however, are significant. First, one cannot shift gears when stopped. This can be very problematic in a city. Next, they require maintenance. Without proper maintenance, they will rapidly fall in to disrepair (though a tune-up will usually fix this). The problem is compounded in that derailleurs are a bit too complicated for the layperson to fix. While problems incurred by a single-speed are relatively intuitive, there are enough screws and barrels on a typical bicycle transmission to frighten your average beginner, and help from the bike shop costs money.

Finally, not all drive trains are created equal. The derailleur is just one of many components in a multi-gear drive train, and there is a cornucopia of different "levels" of components. This will dramatically affect the price of the bicycle. If you see two seemingly identical bicycles selling for two dramatically different prices, the discrepancy is probably caused by the quality and weight of its drive-train components. To go through all the brands and levels of drive-train components would be unpalatably tedious. So,when you are at your local bike shop, ask about the different levels of components they sell. Generally, you will encounter Shimano products, though SRAM and Campagnolo both make quality components. A quality bicycle will have Shimano's Tiagra (road), ALIVO, or DEORE (mountain) components or better.

Internal transmissions are, in my mind, the happy medium for city cycling. The primary benefit is the ability to shift while stopped; this is crucial in maintaining simplicity in an urban setting. Instead of the constant upward and downward shifting for stop signs and lights, the rider can concentrate on the road rather than on his or her chain's position. Another benefit is that modern internal transmissions aren't exposed to the elements, and they don't require nearly as much maintenance as a drive train with a cassette. They are slightly heavier than their derailleur counterparts, though, but this weight disadvantage is more than made up for by simplicity of use. Traditionally, an internal transmission hub only came with three gear ratios, but one can now get eight or even twelve speeds with an internal transmission. They are, however, expensive. Another downside is their noise; some of the models are quite loud and make clicking noises when in certain gears, though not all of them. Also, they can be broken in a serious crash. While a derailleur system isn't exactly tough, if one were to damage a hub with internal transmission, the entire transmission would be ruined, whereas a derailleur or cassette can easily be replaced on its own.

Regardless of whether you chose a derailleur or internal transmission, you will need shifters. Typically, bikes have trigger shifters (clickable shifters mounted on the handlebars) or friction shifters (metal tabs that move up and down on older bikes). However, there are shifters integrated into brakes, and grip shifters that are integrated where you hold the handlebars. The right shifters can greatly increase the riding experience, so make sure you consider your available options when looking at bikes to purchase.

The price ranges of bicycles for different vendors can be summed up only very generally. As a new cyclist, you will have limited knowledge as to what you are looking for, so here's what to expect. In a bike store, you will probably pay $600 at the bare minimum for anything made of chromoly steel, but I would expect to pay closer to between $800 and $1200. One benefit you should expect is a free cable adjustment between one to three months after purchase. Bicycle cables stretch when they are new and need to be adjusted after the first few months of riding. You may also get a free tune-up after one year of riding; this is somewhere between $60 and $100 of savings (assuming you plan on maintaining your bicycle). Sometimes there will be added benefits from the shop you go to: free adjustments, discounts on accessories or apparel, discounts at its café (many bike shops have commuter cafés), etc. Needless to say, there are some clearly identifiable benefits from buying a new bicycle from a bike shop.

If you go with an online retailer, like Bikes Direct, then you will probably be paying between $250 and $1000 for a standard introductory bike. This is a substantial savings, but there are serious downsides. First, you will have to assemble the bike yourself. It's not too hard, but if you find yourself without a set of Allen wrenches, you'll be paying out of pocket for those. Plus, I hope you are comfortable with looking online for how to make basic adjustments, because you will need to make adjustments to some of the cables within three months, and you will probably have to take it into a store if you don't know how. Don't be surprised if the shop owners charge you a high price for labor, as they will know you purchased your bike from an online discount retailer by its brand name. It'd probably be better if you at least know someone who is handy with bikes or are ready to learn.

If you shop on Craigslist, be ready to get savvy. While the shrewd cyclist can find incredible deals on this website, more often than not you will be rolling the dice. I wouldn't feel comfortable advising anyone to spend more than $350 on a Craigslist bike unless you know what you're doing. You can certainly find bikes for less than that, but you really need to know what to look for to take advantage of these bargains.

Finally, remember to budget for accessories and locks. You will need a good lock, helmet, lights, an air pump, a multi-tool, and a patch kit at minimum. These cost money, and when you skimp here, you put your own safety at risk. So remember to budget $100 at the absolute minimum for these. You can save money if you buy them online before you need them; otherwise, you may end up paying much more to get them immediately at a shop.

At this point, you should have a pretty reasonable idea of what you want. Now you need to know what you don't want. You can't check for everything on a used bike, but you can certainly check for the major issues. It is helpful to bring a friend, a length of string at least double the length of the bike, and a pen or marker to any bike evaluation. Keep an eye out for the following five red flags whenever you are considering a secondhand steel bike. Much of this advice applies to aluminum or carbon fiber, but secondhand steel bikes can be of exceedingly high quality and are common.

First, check the weight of the bicycle. This is generally a good indicator of a quality bicycle. An extremely heavy frame is probably made of high-tensile steel, or possibly worse. This means there may be rust or corrosion out of sight, especially inside the frame if the bike was improperly stored. This can cause numerous headaches, from damage to the bike's structural integrity to parts seizing in the frame. You can check for this by looking inside the frame with a flashlight and trying to adjust anything with threading, but if you are buying a used high-tensile steel bike with any serious age, make sure it is very inexpensive.

Next, check for rust or cracks on the outside of the bicycle. If there are any cracks anywhere on the frame, don't buy the bike. Also, any serious paint loss should be a red flag, as it could lead to rust in the near future. Make sure areas around the lugs or welds are rust-free. Rust on the these sections should be especially worrisome because it is potentially dangerous.

You'll want to check the drive train. This, however, can be difficult if you are not familiar with the way a worn-out drive train looks (this is discussed in Chapter 5). If you are unable to assess the cogs and derailleur, just check for any serious rust or significant hub wobbling as it spins, as this is a very bad sign. You should also try and ride it up an incline and check that the chain doesn't jump under pressure. If it does, this is a worn-out drive train that needs to be replaced. A rusted single-speed drive train is not as serious of a problem because the parts are cheap to replace and a lot more sturdy due to the lack of shifting, but make sure the chainline is straight.

Next, check the bearings. There are ball-bearings in the hubs, bottom bracket, and headset. Make sure these all spin smoothly and give little resistance. Bearings are rather inexpensive to replace if they're is all that's wrong with a nice bike, but bearings are fairly sturdy. If they were seriously damaged for some reason, I'd be concerned about a general lack of maintenance, and what other problems might be lurking.

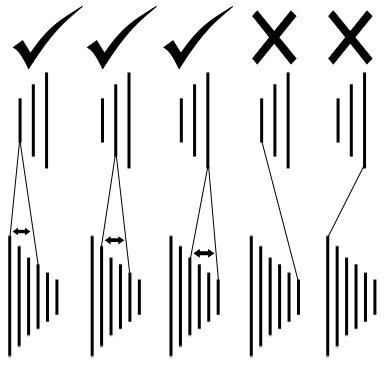

Finally, to be truly careful, you must check to make sure the fork and rear triangle are straight. Checking the fork is simple; remove the front wheel and reset it. While the owner can make a wheel appear straight in a bent fork, if you replace the wheel yourself while visually checking, you'll be able to see if the wheel is off-kilter in the fork, indicating that it's bent. Also, you will need to check if the wheel is true when doing this (give it a spin and make sure it doesn't wobble much), as this might cause a false positive.

Checking whether the rear triangle is straight is a good idea. The easiest method is to test it with a very long string. It's a bit tricky to describe how to do this, but essentially, you want to measure the distance from the front of the bike to each rear dropout. If that distance is equal, then the rear triangle is fine. If there is any large discrepancy, then do not buy the bike as it will probably not ride straight. The way to do this is by taking a string and starting by holding it next to one dropout, then have a friend take the string around the head tube and bring it to the other rear dropout. Hold both ends firm and have your friend mark the center point at the head tube and then where the string hits the dropouts. Then remove the string and pull it taut without the bike to measure the two distances. If your marks line up, then you are probably safe. If there is any serious discrepancy, beware; either the front or rear triangle is probably bent, and the bicycle might not ride properly.

"Nothing is pleasant that is not spiced with variety."

-Francis Bacon5

Once you have a bike, there may be a few things you don't love about it. Upgrading the "touch points" on your bike is a great way to improve comfort. The touch points are your saddle, handlebars, and pedals. Each of these is integral to how you interact with a bike, so they are worth a second look. There are many other ways to improve your ride, too; for example, you might not know about skirt guards and panniers. (The former protects your clothing from getting caught in your rear wheel; the latter is a pack designed to fit on a bike to make carrying things easy.) Utilizing these types of accessories is key for turning a good experience into a great one.

The saddle is, arguably, the most important part of a bike. It is the heart of the three touch points. The comfort of your bike is primarily dependent on frame-fitting and saddle type. Unfortunately, an ill-fitting saddle can cause greater problems than simple discomfort. I strongly suggest getting fitted for an after-market saddle if you plan on riding for any serious length of time.

The first decision is what style of saddle you want. The main things to concentrate on are material, suspension, width, and cutout. Saddle material is generally either padded or leather. Padded saddles are the most common. They are typically just some kind of padding material over a plastic frame. They will usually be covered in either a fabric-, vinyl-, or leather-like material. When looking for a padded saddle, you will want it to be firm, not squishy. The goal is for it to distribute the weight on your sit bones ever so slightly without it pressing into your perineum (between your legs), so stay away from soft padding. Ideally, it will give like a properly inflated tire: firmly. Keep in mind that finding a good fit is tricky, so make sure to ask your mechanic for advice.

Padded saddles are preferable if you live in a particularly wet climate, as rain can ruin leather. They are also good if you are concerned with price. Padded saddles also come in a variety of colors. They are usually black, often white, but there are manufacturers that produce saddles in every color imaginable; I've seen them in plaid, or even sparkling purple, so personalization is extremely easy.

Leather is the other main saddle type. If you imagine the padded saddle as a firm desk chair, a stretched leather saddle is a hammock. The leather starts incredibly tight across the seat; as you use it, it stretches until your weight is evenly distributed across its surface. This essentially gives you a personal, custom fit. This custom fitting is complimented by a leather saddle's aesthetic value. Many leather-saddle manufactures make exceedingly beautiful ones. Some are imprinted with designs and most have warm, rich color tones. The primary downside of a leather saddle is its price. Even the lower-end saddles generally cost more than $100, and the price goes up from there. Another downside is that leather saddles are not typically weatherproof. This means that one would need to use a cover or plastic bag any time it rains or snows; it would also be advantageous to have fenders to prevent saturation from underneath. Finally, leather saddles are, unfortunately, magnets for theft; their nice looks and higher price can mean they will be targeted and must be camouflaged when locked up; it's worth keeping this in mind when considering an investment in a saddle.

Suspension is often found on leather touring saddles. There are two different types of seat suspension: suspension on the saddle itself, or on the seat post. Suspension on-saddle is generally confined to large springs at the rear of the seat. These allow the frame of the saddle some independence. If you have a particularly stiff frame — aluminum, for instance — some type of saddle suspension might work well.

While suspension can help, width is a more important factor when it comes to a saddle's comfort. If your saddle is not the appropriate width, your sit bones won't fall where they should and your butt will not be comfortable. You can have your sit bones measured at some higher-end shops, and you might want to consider this if you are looking to get an after-market saddle.

Narrower saddles can be dangerous if improperly fit. The human body, say, sitting on a chair, will have its weight properly distributed on the sit bones. On a saddle, however, weight con be distributed in between the legs. Unfortunately, the perineum nerve runs between the legs, and too much weigh compressing it can cause the genitals to go numb and potentially cause permanent damage. If your saddle is too narrow, you may be putting the entire weight of your body on very this delicate area. Studies have linked perineum damage from cycling to sexual disfunction6. Make sure you consult your doctor about these potential issues and consider purchasing an after-market saddle. Manufacturers know about these issues and have designed saddles with them in mind. First, there are no-nose saddles; these saddles come in many shapes and sizes, but their unifying feature is that they contact the body only around the sit bones. However, some of them seem quite odd indeed, and may be the result of marketing rather than science. The second type of perineum-relief saddles are those with cutouts. These cutouts leave a gap where your delicate areas are supposed to encounter pressure so as to prevent anything from pressing against your body at these points. Needless to say, I cannot provide any advice as to which of these, if any, actually provides any medical benefit, but I will say if you are experiencing any pain or numbness, it's probably best to talk to your doctor immediately and see if anything can be done.

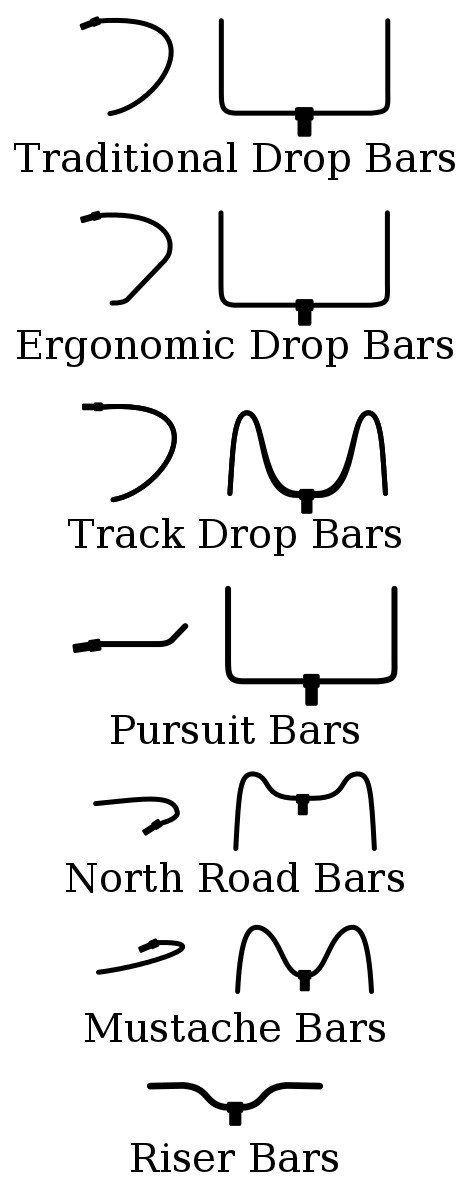

The easiest way to individualize your bike is with a new set of handlebars. There are many to choose from; if you have a road bike, you can choose from traditional drops, ergonomic drops, or track drops. A city bike can use everything, from drops to straight bars, swooping North Road bars, or even pursuits (also called bullhorns). They are all relatively inexpensive. The only thing you need to take into account is whether they are compatible with your stem, shifters, and brake levers. Getting the sizing of your stem is a relatively simple task; you can just go to your local bike store and they will measure it for you. Getting bars that are compatible with your brake levers, on the other hand, is a different story altogether. It is somewhat straightforward, and somewhat a judgement call. Can you use long pull-brakes on mustache bars? Probably, but it would would certainly be a bad idea to use them on riser bars. Having accessible, easy-to-use brakes is obviously important; make sure you talk with your mechanic about yours before buying new handlebars.

Pedals are a relatively inexpensive improvement. There are metal pedals for added strength, big, fat BMX pedals, or one of the myriad versions of clipless pedals for improved performance. I'm of the opinion that BMX pedals are ideal for the casual rider7. They are typically very inexpensive, but still light and designed to be strong. They come in a wide variety of colors, so matching your bike is relatively simple. For added support, you can buy thick straps that hold your feet in place. So if your feet are causing you any discomfort, consider getting a new set of pedals.

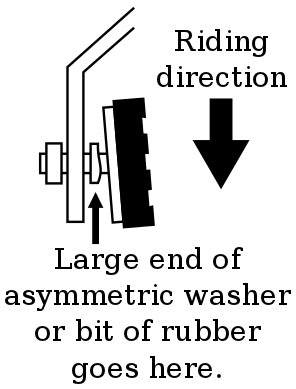

Fenders, skirt guards, chain covers, and kickstands are all optional accessories with which you can individuate your bicycle. If you live in a rainy area, you will most certainly want fenders. Skirt guards have a hidden benefit in cold climates, because jackets often hang low enough to get caught in, or at least be dirtied by, the rear wheel8. These can easily be jury-rigged from a standard plastic fender by punching holes along the top and tying thread or mesh between the rear dropout and fender. Just be careful to trim anything loose so it won't get caught while riding. Chain covers are perfect for the businessman who wants neither to stain his slacks nor to roll them up. Kickstands, contrary to their childish image, are a borderline necessity for serious cargo cyclists, and often come with a beautifully constructed double kickstand that holds the rear wheel aloft (useful during repairs). Rear racks, along with panniers, make hauling groceries easy. The tiniest of riders can carry loads of supplies if panniers are utilized properly.

Bells and lights are significantly more necessary, and are required in many jurisdictions. There are hundreds of types of lights to suit any cyclist's needs: helmet-mounted, frame-mounted, or made from stretchy silicone to fit anywhere. There is significant choice, also, with bells, from the traditional large bell with its distinctive ring to specially designed Sögreni (Danish) bells that are as practical as they are beautiful9. Needless to say, you can spend a lot of time (and money) getting your bike exactly how you want it.

"A day or two since, a gentleman in Chicago, who has been practicing on a velocipede, for some time on the sidewalks, came out upon Indiana-avenue, and throwing down the gauntlet of defiance, dared a street car driver to race with him to Thirty-first street, the terminus of the track. The challenge was accepted by the car driver, although the latter had several lady passengers on board. The race began auspiciously, the horses being driven at a furious pace. The velocipede soon gained upon its competitor, and bade fair to distance it, when an unlucky crack in the sidewalk received the forewheel, leaving the other, in obedience to the law of its momentum, to turn a summersault, throwing the rider into the gutter. The car won the race on a 'foul.'"

-The New York Times, January 15, 186910

You are traffic, and if you plan on riding a bicycle around town, it's probably a good idea to have a reasonable knowledge of how to act. Unfortunately, there is no widespread cyclists' education to train riders, and there are many misconceptions about how to ride on the streets. Following some general guidelines, it's relatively easy to get around town in a safe, quick, and efficient manner. Now, before I begin, lights and a helmet: use them. Use lights at night, use them in the early morning hours, use them whenever it's dark. Get extra batteries for your lights; keep some in your bag. Reflectors suck; get lights. Use lights. Buy a helmet you will wear. It's worth spending a little extra money on one so that you won't hate it. I shouldn't even have to explain this.

Improving the way we look at our cities is a great way to prevent conflict. Think of the map of your city. If you are like me, you are thinking of roads, primarily high-speed, high-traffic roads. However, if you want a safe, pleasant cycling experience, it helps to create a gestalt shift in the way you see your city map. What do I mean? Cities with large transit systems have clear, alternative maps. When taking the subway uptown in New York City, one doesn't have to remember which subway line runs along Broadway (it's the N/Q/R trains below Times Square, and 1/2/3 above). In fact, in the subway, one doesn't think of routes in terms of roads at all. On subway maps, the roads almost disappear beneath the train lines. Now imagine you need figure out which way to take subway, but you only have a road map. You look the road map, then superimpose the subway map onto it in your mind. You "see" both maps, and you can "flip" them back an forth in your mind. This is a gestalt shift. This is useful very when looking at your city map in terms of cycling.

An automobile-centric map is typically the default when people visualize their city. Everyone has already learned it. What is intuitive about an automobile-centric map is that road size on the map typically correlates to actual road size. "You can't miss it" is an expression that is common for driving directions because major routes are physically large. Unfortunately, bike maps are quite the opposite. Safe routes are on small, generally unnoticed roads, hidden away in neighborhoods or parks. The reason new cyclists don't know of these routes is precisely because they aren't roads that are often driven on. For example, when I ride across Austin, I obviously don't take Mopac or I-35 (highways); I don't even take Lamar or Congress (major avenues). I ride on small, neighborhood roads, away from traffic all the way across town. However, I am only able to do this because I know the bike routes, cycle paths, and other facilities. I spent some time learning them. Ask someone in Austin if he knows where South Lamar is and there's a good chance he can tell you in detail, but ask him where Kenny Street is and he will probably have no idea. These roads are essentially parallel, but the first is a major thoroughfare (that can be frightening even with its bike lane), while the other is a bike-friendly route on a small, neighborhood road.

Now, if you are a new (or potential) cyclist, you probably think of the roads you'd typically drive on when contemplating a route, and could be terrified at the prospect of having to interact with the associated traffic. Of course, you probably don't need to ride on those busy roads at all. A bike map can calm those fears by showing the appropriate neighborhood routes with low traffic and slow speeds, though most of these maps could be improved. The best part is that these alternate routes probably won't even be out of the way; they might even save you some time. So drop by a cycling shop and see if there is a bike map of your city, and keep it in your bag or by your bike. It'll be useful if you need find an new route across town.

Unfortunately, cyclists must always ride defensively. Even though drivers can see you, often, perhaps through no fault of their own, they won't. Bicycle advocates have pointed out that there is safety in numbers when it comes to cycling11. This is not to say that riding in groups is safer than riding alone, but that drivers tend to see only what they expect to see. Thus, if there is a high prevalence of cycling in a community, the drivers in that community will literally be able to see and interact with a cyclist sooner and more safely. The other side of the coin, unfortunately, is that in less-cycled communities, automobile drivers may not see you, and you need to be wary of them; they can be quite dangerous with their blinders on.

Watch out for doors. The verb "doored" refers to when someone opens the door of a parked car immediately in front of a cyclist, causing the cyclist to swerve into traffic or crash into the door. This is probably the most serious danger that most new cyclists and, unfortunately, most people, don't know about. Cyclists are typically directed to the right side of the road where cars are parked; unfortunately, this is where people most frequently open doors, even if a bike lane is provided. Because of this, bike lanes on one-way streets are now being placed on the left side, as the number of passengers exiting cars here is orders of magnitude smaller. My advice here would be not to ride very quickly when in between traffic and parked cars. Check cars' rearview mirrors to see if anyone is in the driver's seat. Be aware of cars that have just parallel-parked in front of you; their drivers will probably be exiting. Be wary of cars that are idling or have their brake lights on. You never know when the driver may exit, but you do know the car is occupied. Just knowing a door may open is half the battle; use the whole bike lane, it's wide for a reason. Finally, take the lane when necessary. That is, if you feel unsafe, use the full lane. This is legal in almost all jurisdictions.

There are also more subtle aspects of interacting with cars. For example, make eye contact. Yes, get used to looking through the windshield and looking the driver in the eye. There is a person in that car; study him. Is he looking at you? Is he texting someone? Is he distracted? If he is looking at you, he probably sees you; if he isn't, he definitely doesn't, so proceed with caution. This simple trick is the best piece of defensive cycling I know. Always beware of cell phones, because distracted drivers do strange things. Look at them as you interact with them. It is not just a car, it is a person in a car.

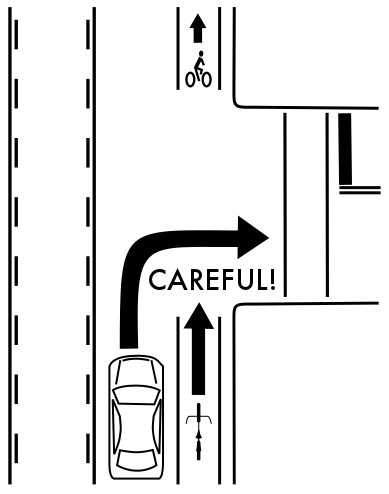

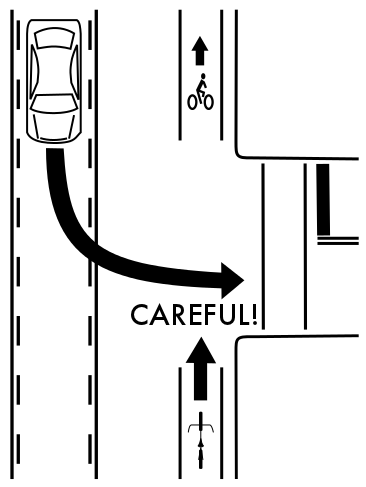

There are also times at intersections when cars' actions should not be trusted. The two main scenarios one should look out for, are the 'right hook' and the 'left cross'. The right hook is the when a driver suddenly turns right into a cyclist at an intersection. There is really no way to anticipate this, but it's best to be aware of automobiles near you at an intersection. Try to avoid riding through the intersection when in the blind spot of a car. It's also a good idea to keep an eye on the front tire of cars that you think may be about to turn right it front of you. It's actually much easier than it seems.

The left cross can happen when a car opposite someone in an intersection turns left inattentively. They may be trying to sneak through a gap on a busy street, or they may be completely oblivious to cyclists altogether. Either way, be ready to avoid a collision of this type. Slow down before the intersection and try to see if this driver is anticipating you approaching. Have you made eye contact? Are you riding through just as a gap in traffic is created? Keep these things in mind and proceed with caution. It will become second nature once you start checking for it, trust me.

Always take the full lane when needed. Most state laws instruct the cyclist to stay as far to the right as is "practicable." Now, what "practicable" means is obviously intentionally vague, but I can tell you, it is rather "impracticable" to stay dangerously close to the curb, where damage to the pavement could leave you stuck between the curb and a passing car. Generally, I would suggest riding in the right tire-mark, but also taking the full lane when appropriate. This allows plenty of room for automobiles to pass when it is safe, but it also leaves the cyclist some enough space if a distracted automobile driver were to (accidentally) pass too close, while (accidentally) discharging the horn and (accidentally) shouting something inaudible while passing (these accidents do happen occasionally). While this might create a dangerous situation if the cyclist where up against drainage or a curb, taking the lane leaves the cyclist plenty of room to maneuver away from the car and to signal to the driver that he or she may consider a safer passing distance in the future.

"Undertaking" is a term for passing on the right, especially in that small space between the car and the curb. This is opposed to overtaking (passing on the left). Undertaking is extremely, and surprisingly, dangerous. Here, you won't know if they're turning, and they won't know you are there. The danger of undertaking increases with the size of the vehicle. Drivers of large trucks or busses have little or no chance of seeing you when you are on their passenger side. Obviously, this is especially dangerous at intersections, even when stopped at a red light. Always watch the front tire of a car when passing, on either side, especially at intersections. It is a better indicator of whether a car is turning than the blinker, I assure you.

Filtering is quite similar to undertaking. Filtering is when, at a red light in heavy traffic, a cyclist will split lanes to advance to the light. While I'm not going to outright tell you not to do this (I'd be lying if I said I've never done this), filtering should be discouraged, especially in dangerous areas. The dangers are, first, that the light may change when you're advancing; this can put the cyclist tightly in between two moving vehicles. Second, there is the danger identical to that of undertaking; if one advances to the right of a car intending to make a right turn without signaling (what's the harm?, they will presume, as they're in the far right lane with no one to yield to), they can turn into you without even realizing.

Again, remember that many drivers just don't pay as much attention as they should, especially with cell phones in the car. Others just don't understand the rules of the road. These drivers may be aggressive yielders. Expect to encounter aggressive yielders frequently in traffic. What do I mean by "aggressive"? The textbook example is a crosswalk that is not situated at an intersection. Drivers may be either ignorant of their duty to yield or intentionally ignore this duty; regardless, it is quite common (and probably safer) for pedestrians to yield to drivers in these crosswalks because of the risks involved with crossing as a two-ton automobile rapidly approaching. It is prudent to yield to aggressive drivers even though you have the right of way. Be careful, especially in areas that involve merging. Be careful when drivers have yield signs. Be careful at rotaries. The negative outcome is too great, no matter how small its probability of an accident. There is just no way to eliminate this behavior under the current transit paradigm.

Communication between vehicles can be difficult. You know who I notice are terrible at communicating on the road? Cyclists. Typically, the Spandex Crew (sorry, guys ... Lycra) is quite good at communication, as well as the over-30 crowd, but the vast majority of cyclists don't signal. Signaling is expected of automobiles for good reason; automobiles kill people. But it should also be expected of cyclists for the same reason; that is, because automobiles can kill you (plus it's polite), so be sure to signal when changing lanes or turning. Unfortunately, the proper hand signals are generally unknown to most drivers, but they will understand if you just stick your arm out in the direction you plan to go. You can do the arm up thing for turning right or the arm down for stopping, but I doubt if many people will remember these from Driver's Ed.

Also, remember to keep your eyes on the road. Cars behind you can see you. While I understand why people have this (mostly irrational) fear, it's really unnecessary. Few accidents are happen this way, and assuming you follow some general precautions (taking the lane when needed, lights, signaling, reflectors, etc.) it's better to direct your attention to other important causes of accidents. Generally, keeping your eyes forward, looking at the pavement, and concentrating on doors and cars turning are areas where you should be concentrating. Road conditions cause accidents. Potholes, loose gravel, or road work debris can sent you for a tumble without even encountering an automobile. The velocipede rider from the beginning of this chapter lost his race against the street car because of such an accident. So remember to concentrate on your surroundings, and slow down if you start to feel unsafe.

Another group one interacts with on the road is other cyclists. The most annoying thing you may encounter with other cyclists is salmoning in the bike lane. What is salmoning? In the same way that salmon swim against the current, bicycle salmon are those who ride against traffic flow. While this isn't too much of a problem in most areas, and is even generally legal in places (notably France), it does become a problem when it happens in the bike lane. The problem is that, while a bike lane on a one-way street is ideally on the left side (so as to reduce the chance of being doored), our convention for passing on the right forces the law abider into traffic, and thus, potential danger. For this reason I sternly hug the left side of these one-way bike lanes when encountering bike salmon. It can end up as a mild game of chicken, so make sure that you make eye contact and try to communicate with them. They can see oncoming traffic; you can't. It sometimes doesn't go over too well, but I'm not exactly worried about getting a hard time from someone who is putting my safety at risk because he or she can't be bothered to ride his or her bike one stupid block out of the way. I mean, can't people really be expected to take the extra fifteen seconds to actually follow the city's set bike routes? They are saving seconds (even up to a minute) off of their commute, so one can understand why they would need to cause their fellow cyclists grief; those precious seconds are the difference between the yellow jersey and second place! </rant>

As the culture of cycling becomes more prevalent, interactions between cyclists and pedestrians will become more respectable, but they are currently strained to some extent. At crosswalks, pedestrians have the right of way; be aware of them. It may be easy to avoid a pedestrian in a crosswalk, but being an aggressive yielder on a bicycle is still annoying and antisocial. If it is safe to pass, do slow down and acknowledge to the pedestrian that you see him or her, and don't inhibit his or her path. If you are turning at a green light, let pedestrians cross before advancing, especially at busy intersections. It's basic follow-the-rules type stuff that any pro-social rider would intuitively follow; however, it still seems to be a problem in many cities.

Now, there are pedestrians who behave badly, too. The main danger posed by pedestrians occurs when they step out in front of you without looking. This will happen frequently in intersections, in bike lanes, on trails, and even just in the street. Be ready for it. It's difficult for a culture to change, and pedestrians have been comfortable not having to watch for bicycles for many years; their ears listen for cars, and their eyes have been lazy. I, too, have been guilty of stepping into the bike lane without looking, and that is coming from a cyclist who usually watches out for bike salmon when crossing the street. A change to this behavior will take time, and there are a few solutions. You can simply shout when someone is stepping out in front of you, but you could also use a bell or a toed-out brake.